How to make high-speed rail a reality in the US, Part Two 🚆

Introducing "The Ographies+" and a quick trip around the world 🌎

Climate Solutions // ISSUE #87 // HOTHOUSE 2.0

Now see the complete high-speed rail series here: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Final Installment.

Hello dear Hothousers,

I hope this newsletter finds your September ramping up to a cozy fall (provided you’re in the Northern Hemisphere). In mid-August, I ended up joining the most recent wave of COVID infections, which knocked me out for a good week. So today we finally pick up where we left off.

In our last issue, transportation guru Sam Sklar gave us a glimpse into some of the historical and political constraints shaping the contemporary state of passenger rail in the U.S., i.e. Amtrak doesn’t own the rail it operates on, and the transcontinental rail corporations that allocate airtime to Amtrak passenger trains are disincentivized from offering more.

Today, we take a look at the characteristics and opportunities informing international High-Speed Rail construction that might offer insights for success here in the U.S.

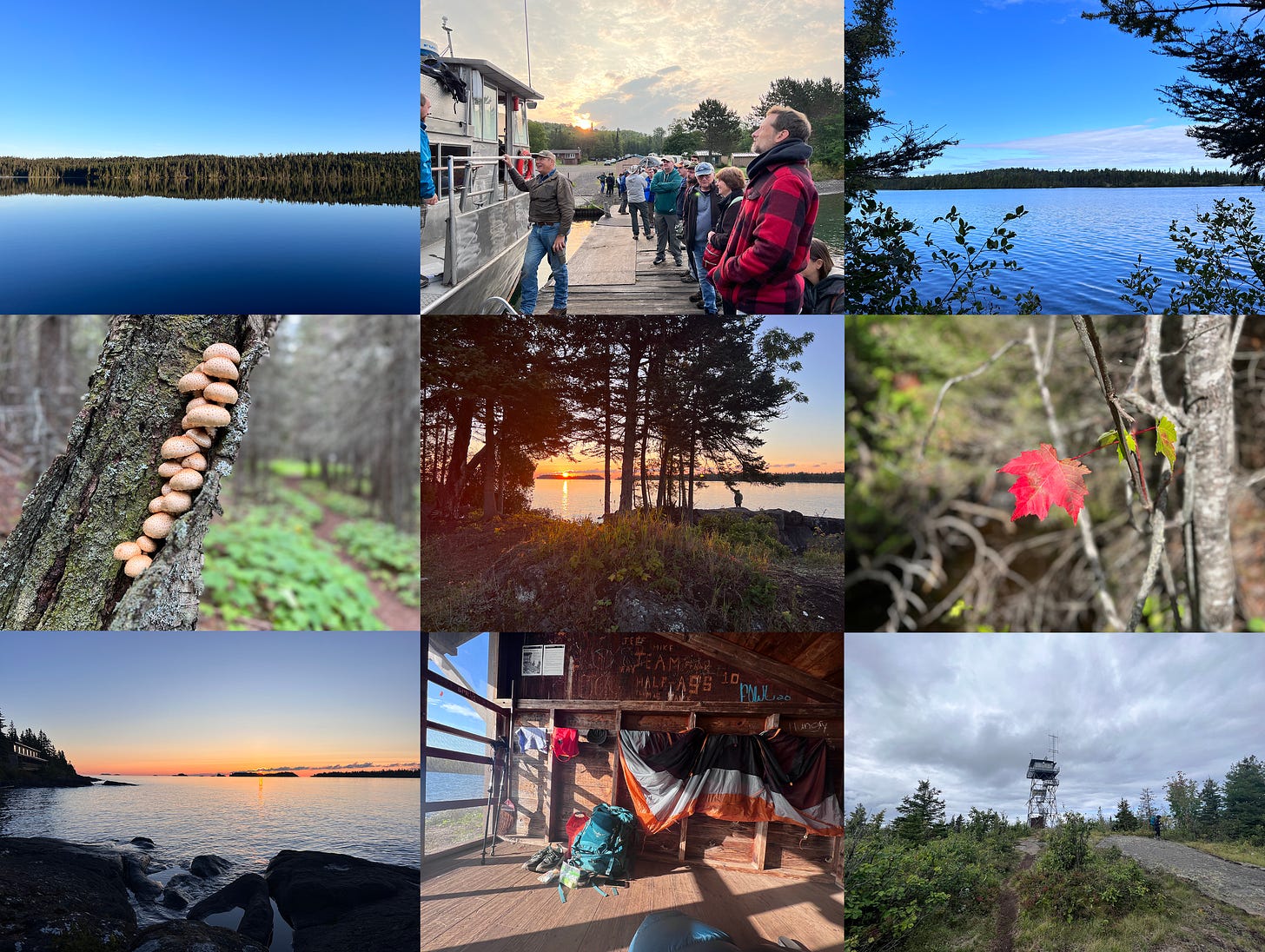

At the start of September, I also enjoyed a trek home to Duluth, Minnesota, including a five-day hike of the remote Isle Royale with my 68-year-old mother. Largely out of cell service, it was an awesome opportunity to slow down. I look forward to sharing a bit more in the next installment. For now, please enjoy a few pictures.

Cheers,

Editor-in-Chief

From ‘Train Daddy’ to Japan

By Sam Sklar

It’s time to talk bluntly about the problem of building high-speed rail in the U.S. Why haven’t we pulled it off? It’s not for a lack of ambition from dedicated professionals; we have that in spades. For instance, Amtrak recently hired Andy Byford, the former head of the MTA in New York City as well as former head of Transport for London, aka “Train Daddy,” to lead its High-Speed Rail planning efforts. And I myself am a trained transportation planner who’s worked alongside hundreds of hardworking individuals inside and outside government struggling with this issue on a day-to-day basis for nearly a decade. Nor is our problem that too few people care about HSR. The national media and the blogging universe write (or vlog)1 about the business2 of High-Speed Rail fairly often; Xwitter is full of yea and naysayers. Still, our problem has many parts. Namely, it’s unbelievably hard to land the right alchemy of what I’m calling the “ographies-plus” at the right time.

What I mean is this: In all instances, there are seven challenges (aka the ographies+) that any future high-speed rail project must address in order to be successful. Thus, the first portion of this installment will give an overview of the seven ographies+, while the latter half will give a brief overview of how high-speed rail works in China, Japan, and Western Europe. Passing our present challenge through these two lenses will help us identify the kinds of insights that could—just maybe—give us the trappings of a playbook for rolling out HSR here in the U.S.

In essence, we must learn what we can from our contemporaries across the globe while recognizing we will need to adapt best practices according to our own unique situation.

The Ographies+

As I mentioned, any successful HSR project must address all seven ographies+. It’s an “all, not some” situation we’ve found ourselves in, and to even start the analysis we’ve got to define our terms.

Demography, Geography, Topography

Demography:

This is an academic term that boils down to the study of the “who”, “what”, and “where” of a population.

What’s the most important demographic factor to consider in the context of rail operations? Something known as an “exponential” density factor—the closer a person lives or works to the train station, the exponentially more likely they are to take the train and increase the value of the rail investment to the rail company.

This data point reveals how many people live near enough to a train station to justify the cost and effort of building any train, let alone HSR.

Given the huge costs of building out HSR,3 to help narrow the scope of potential opportunities to build, we should also fold a question of economic gravity into demography: How might this rail service either directly or indirectly affect Regional Gross Domestic Product (RGDP)? In other words, as a society, do we want our equation for determining the best place to build to give more weight to the place with the highest GDP already, or to the place where GDP could use a boost via new connectivity? It’s not an easy question—and there’s no simple answer. The only way to get to its core is through constant communication with stakeholders. But…who are these people with a stake in the project and how do we find them? Just having the alignment of a rail system isn't good enough. It has to actually solve a problem for relevant stakeholders.

Geography:

This is the study of the actual size and spatial characteristics of a place.

Geography, as it relates to rail, entails understanding the distribution of populations across the vastness of the United States. Compared to other countries, save maybe Russia, Canada, and Australia, the U.S. is enormous and mostly empty almost everywhere. Especially west of the Mississippi River, distances between cities are vast. The 440 miles between Washington, D.C., and Boston are reasonable for a 200 mph train service. The 2,777 miles between New York City and Los Angeles are…not.

Topography:4

This is the physical composition of a place—think the attributes that would prevent a railroad company from building as the crow flies from point to point. Mountains provide technical challenges that often spill over into political ones.5 Tunneling through or under hard rock adds engineering challenges and can explode budgets and timelines.

The choices are then many: do we build this rail line as directly as possible, do we maneuver it around a mountain—and if that’s the case, which way? How do we pick which mountains we skirt or tunnel through or which rivers we bridge over? Who gets to make these choices?

The Rest: Funding/Financing, Politics, Ownership/Power, Connectivity

Funding/Financing:

How do we pay for what we want? For rail in the U.S., we’re at a crossroads: there’s more money now than there’s ever been to build new rail but there’s (so far) little progress to show for it. New public dollars (i.e. taxes) are available now—thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL)—to spend on rail projects; up to $8.9 billion for projects along the Northeast Corridor and another $4.7 billion in grants dedicated to rail projects, including, but not limited to, high-speed rail beyond the Northeast Corridor. If we don’t spend it on projects that make a tangible difference in people’s lives, though, one could reasonably fear that the public will eventually run out of patience if their tax dollars are spent repeatedly on “studies” or “designs” with very little actual rail to show for it.

Curiously, there does seem to be a concurrent renaissance in private investment in U.S. rail and surrounding land development (as Brightline and Brightline West show), so there might be appetite and capacity to raise additional capital, leverage it with cheapish debt, and pair it with IRA/BIL money to build out new HSR services.

Politics:

Transportation is usually a lower-priority political issue, and when we do talk about it in the national context, the conversation is usually dominated by a discussion of spending on road first and rail last.

In the U.S., rail politics, like all politics, is a function of federalism, i.e. the partitioning of power between the U.S. as a country and its 50 individual states. To pull off HSR, we can’t have a single state veto a national priority, especially a state like Wyoming, whose population density wouldn’t necessarily demand an HSR stop, but whose landscape we might need to route a corridor through.

We need a national rail network to reflect the interstate nature of regional HSR. This wicked problem is why it’s important for proponents and friends of HSR to fight for better rail service and for us to continue to exert pressure on those in power.

Ownership:

Property rights and protecting them are at the center of the American experience. The question often overlooked in public discourse of HSR is: who owns the rail or who owns the land under and around the rail? As we covered in the last dispatch of Hothouse, we know that Amtrak owns about 3% of all of its tracks and is beholden to the whims of freight rail operators who hold enormous power and are subject to very little federal oversight.6 If we’re to build HSR, any authority would likely have to build new tracks on or around privately owned land, whose owners are naturally protective of it.

Connectivity:

The rail can’t just go from nowhere to nowhere simply because the land is cheap or available. It also has to be usable. It is essential that HSR connects to regional rail and/or local transit systems—you have to be able to get to and from the HSR without three additional transfers. We call the beginnings and endings of journeys “first- and last-mile solutions”, and they have to be considered as part of a full trip; HSR is just a huge middle chunk, but if there’s no way to offload to a feeder system that isn’t a car or low-frequency transit system, the trip becomes less and less convenient, and HSR’s competitive advantage with driving or flying all but disappears.

A quick trip around the world: China, Japan, and Europe

When it comes to HSR, we’re behind our contemporaries in Western Europe and East Asia in almost any category we’d want to measure—but it’s not all bad. There’s still a ton to learn from the many people and organizations that have now spent decades building HSR.

It’s important to note our international counterparts operate under a different constellation of “ographies+”. As a result, “best practices” doesn’t mean that the practices are the best; it means that these are the best ways to build and communicate given the resources and context of a given place. Thus, we should seek to learn what we can from our international counterparts and contextualize insights so we’re learning best practices for our unique situation: low on experience, high on need.

Let’s start in China.

China: 130,000 km of High-Speed Rail in under 80 years

In less than 80 years, China’s built the equivalent of half the U.S.’s entire rail system that’s taken us 200 years+ to build, much of it high-speed. It’s a remarkable achievement. What more can be said about this feat except that Chinese infrastructure is beholden to the will of the grand state and the grand state only: if it is the will of the Party, barring a technological or fiscal calamity, the whole country will be covered in HSR as quickly as possible.

As a result, the China State Railway Group Company—a state-owned firm—has built nearly 130,000 km (~80,000 miles) of rail since 1950, with about 30% of it considered international high-speed caliber, and the firm plans to build 50,000 km more.

The pros: China has built and can build connections to any of its cities with little-to-no political resistance and minimal cost friction. Second, they have generations of experience building HSR.

The cons: The Chinese government doesn’t take land-use planning as seriously as a rail network of this caliber requires. As a result, China’s passenger rail systems often fail the connectivity test—one of the seven key “ographies+” mentioned above. Beijing South—a massive, airport-like junction in southwest Beijing is connected to a single metro line. Getting to the downtown business district is a multi-leg journey that can add up to an additional hour to a trip.

Takeaways and Applications in the U.S.:

China’s land area is about 2% bigger, but its population is nearly three times the size, and lots of it is concentrated in cities—at least 100 Chinese cities have a population of over a million people. The U.S. has 10. The population density naturally supports rail and HSR in China whereas it simply does not in the U.S.

Insight: There’s a sweet spot for HSR, and while the U.S. is too vast and empty to make the case for rail for long-haul trips, there are certain city pairs that make sense: New York to Chicago, San Francisco to Los Angeles, Chicago to Minneapolis. Think where 400 miles is an easy tradeoff to make between a rail, car, or plane trip.Insight: China’s confidence to build rail today is supported by their trained workforce and decades of civil engineering experience. By contrast, we haven’t built more than a few rail lines in the U.S., and not at at any kind of scale, for nearly a century. As a result, our institutional knowledge is mostly lost to the wind. If we are serious about keeping up with China-lightning pace in the future, we need to prioritize rebuilding our institutional knowledge...decades ago.

Given all of China’s institutional knowledge, we also could, in theory, call on China to help. Japan: a fully built-out and intricate, somewhat privatized system

Let’s move on to Japan, which has connected its cities with some of the fastest high-speed rails in the world via the Shinkansen (aka: the bullet train). They didn’t get there without a fight, and there is ongoing competition among transportation modes—namely aviation.

JR—Japan Railways Group—is in fact nine distinct rail companies, four of which are publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange; another two companies provide research and IT services off a combination of public and private financing. The Japanese government maintains ownership of the final three companies, one of them responsible for national freight.7 Each passenger rail company operates its own service and shares reciprocity across the entirety of all the JR operators. More information and deeper analysis by Seung Lee, author of the very excellent “S(ubstack)-Bahn,” can be found here.

The pros: The Japanese have demonstrated that accessibility is a right they’re willing to pay for. The Shinkansen connects even to faraway points, at a loss to JR-Hokkaido, which operates on the country’s least populated main island in the north. Japan is a lot smaller than the U.S., though the Tokyo-Sapporo city pair is longer than New York-Chicago, Los Angeles-San Francisco, or Beijing-Shanghai. It also passes through some pretty gnarly mountains. The Japanese are tunneling experts as a result.

The cons: This quasi-privatization came at a great cost to labor, even though some studies have argued that privatization spurred productivity and economic growth.

Takeaways and Applications in the U.S.:

Regardless of their proclivity to build, Japanese rail developers still have to follow the same ographies+ as any other country. JR, however, sets a good example for regional rail construction and operations procedures. By separating JR into six geographically-fenced companies, the network is able to sustain ridership across risk profiles and operating procedures. Lines that serve dense Tokyo and Osaka are fundamentally different than those serving remote Sapporo. The companies do connect to one another and share schedules and fare reciprocity where applicable, which enables easy, nationwide travel for riders.

Insight: Taking the idea of building HSR in city pairs a step farther, seeing the U.S. as an aggregate of regions—larger than states, but smaller than “the whole U.S.”—makes sense. We’ve got to shrink our ambition into bite-size clusters, at least for now.Insight: Curiously, one of the three government-owned rail companies that run Japan's freight lines serves as the inverse of U.S. freight operations. Where Amtrak runs passenger rail services on top of rails owned by private freight companies in the U.S., the Japan Freight Railway Company runs nationalized freight on top of rails largely owned by privatized rail companies in Japan. (Mostly) Western Europe: A connected network, but challenges persist

Europe is coincidentally almost the same size as both China and the U.S. Its cities are smaller than China’s and denser than those in the U.S.

European cities largely squeezed car infrastructure retroactively into centuries of pedestrian- and buggy-based urban development. As a result, for traveling between many places in Europe, train travel saves time, money, emissions, aggravation, you name it. There are of course complementary aviation and road networks, but rail reigns supreme.

The pros: It’s possible and expected to travel to most places in Europe by train because of decades of development and cooperation. Each country built its own rail system, but the incorporation of the EU has made it relatively easy for each country to subsequently connect to one another’s rail networks through rail pass programs like Eurail.

European cities are mostly old and relatively dense, so it’s also often pretty obvious where rail companies should build and buff up. There is also political will to support rail: France even recently banned domestic plane travel where there exists a two-hour train ride and, in the EU, there’s hope that other countries will follow suit.

So far, Europe’s HSR development appears to be severely limited more by topography than any other factor.

The cons: It’s not as easy as “if you build it they will come.” Before we get too enthusiastic about the glory of intercontinental rail in Europe, it turns out accommodating dozens of countries operating on their own rules makes for a disastrous user experience (e.g. no necessarily centralized place to buy tickets for multi-leg journeys), scheduling oversights, and a headache for technical transfer (dissimilar track gauge; different electrification systems).8 Remember: these interoperabilities are a result of ex post facto agreements, as opposed to joint planning and construction from the jump. Buyer beware.

Takeaways and Applications in the U.S.:

Insight: At least we can start building relatively baggage-free. In a rare win for U.S. passenger rail, we don't have to deal with some of the same holdovers that Europe's soldered-together one does: we’ve mostly standardized scheduling, track gauge, and electrification issues. But, as we’ve seen in the Bay Area, convincing neighboring agencies to reciprocate service and fare payments is still easier said than done.Coming up

The next dispatch in this Hothouse series exploring HSR we will take a look at three ongoing HSR projects under development in the U.S.: California High-Speed Rail, Texas Central, and Brightline’s direct descendent, Brightline West. Much has been said or written about all three and each is in various stages of project development. The one thing that connects them is that there’s no track in the ground for any of them yet. Progress and process change for each project almost daily as the three try to navigate complicated development challenges.

These projects and their progeny are essential as proofs of concept that we can build again in the U.S.; that we can recover institutional knowledge to make significant strides in achieving transportation justice; that we can deprioritize car supremacy and reinvest in the future of our planet’s environmental security via a future rooted in shared steel.

And, as is Hothouse 2.0’s modus operandi, we’ll broach what you, the individual, as well as organizations, can do to support building it in our lifetimes.

Let’s get moving.

Hothouse is a climate action newsletter edited by Cadence Bambenek, with copy-editing by Peter Guy Witzig this issue. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read. Follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Thank you to the readers, paying subscribers, and partners who believe in our mission. We couldn’t do this work without you.

Here’s an interesting take from Reece Martin, who often vlogs about different transit/train projects.

Here’s one written on August 30.

Alternatively, if we make it a national priority to connect communities by rail of all sizes no matter the size, then the density question becomes moot. That’s a whole other ballgame.

To a lesser extent hydrography: the study of water affects some travel, but we’re pretty effective bridge builders and levee crafters.

They don’t call it moving mountains for nothing.

Mainly from the Surface Transportation Board, which has the power to convene parties via arbitration, but has very little authority to compel any one side to adhere to any decision.

Three of which run freight, IT services, and research.

Coincidentally, Wendover Productions just released a similar video about rail vs. plane operations in Europe. These two videos are unrelated and have come to fairly different conclusions, which is interesting in and of itself, but out of scope for this piece. I suggest watching both and coming to your own conclusions.

I appreciate you sharing this thoughtful piece. I was unaware of this feature. Really awesome! https://gorillatag.io

Funding and political will are key just like patience and precision in https://blockyblast.io gameplay!