The hard and soft power behind Hawaiʻi’s regenerative travel movement 🌴⛵☀️

The rules of travel are being rewritten

Climate Solutions // ISSUE # 94 // HOTHOUSE

By Michele Bigley and Cadence Bambenek

A record-breaking 10 million tourists flocked to Hawaiʻi in 2019—that’s more than seven times the Aloha State’s entire population.

But as the throngs of tourists have piled up, the archipelago’s environment and culture have both grown more fragile by the day. In 2019, 13 beaches in Hawaiʻi tested positive for 18 toxic sunscreen chemicals known to kill corals and fish. Meanwhile, a housing crisis forced many Native Hawaiians to choose between working multiple jobs and living in overcrowded homes—or relocating elsewhere entirely, to somewhere like Las Vegas or Oregon.

Hawaiʻi is a microcosm for the world’s beloved and beleaguered; from Venice to Ko Phi Phi, bucket list destinations are being loved to death.

In 2020, Hawaiʻi, for one, took the first step to flip the script.

The path paved

The path to the overtourism of Hawaiʻi was first paved more than a century ago.

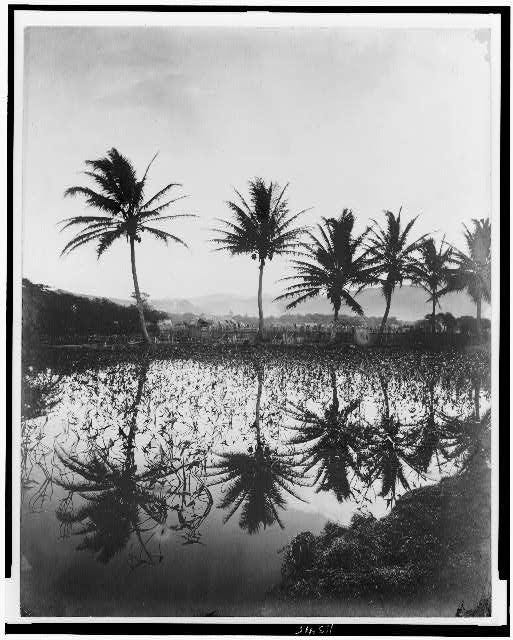

Passenger steamboats first arrived in Honolulu in 1902, delivering well-to-do tourists from San Francisco for weeks-long stays of beach lounging and volcano trekking. Colorized photos and a newly minted tourism promotion bureau enticed visitors to make the voyage.

By 1935, radio waves carried the magic of Hawaiʻi—think sliding steel guitars and crashing waves—into the living rooms of millions across North America and Australia. With the dual arrival of statehood and jet airliners in 1959, annual arrivals hit 250,000, then rocketed to six million by the 1980s.

But as the years have gone by, critics have argued that the tourism industry increasingly caters to outsiders at the expense of the very environment and culture that drew them in the first place.

By 2018, two-thirds of Hawaiians agreed with the sentiment “This island is being run for tourists at the expense of local people.”

A turning point

Just as negative local sentiment toward tourism began to boil over, the world was finally beginning to give proper attention to the climate crisis.

In 2015, the United Nations formally committed to 17 Sustainable Development Goals, aspiring to tackle global challenges like poverty, hunger, and the climate crisis. When the UN looked to identify models for the rest of the world to follow, with its strong global brand and its own sustainable development-inspired Aloha+ Challenge already well underway, Hawaiʻi was a natural choice.

Hawaiʻi became a Local 2030 Hub in 2018, joining the likes of cities in Sweden, Brazil, and the UK. The pressure was on.

But just as the Aloha State was positioned as a sustainability model, the pandemic delivered a stark reality check.

While the onset of the COVID-19 lockdowns returned the islands and ocean to repair, seeing the homecoming of many fish to Hawaiian shores and offering a reprieve to those living on land, the lockdowns also blew open the depth of Hawaiʻi’s economic dependence on tourism. During the height of the pandemic, 40 percent of Maui residents found themselves unemployed.

Hawaiʻi was being forced to reckon with the reality that it could not sustain the sheer quantity of tourists who wanted to visit, while simultaneously being dependent on them.

Step One: A new roadmap

Beyond alluring marketing, the contemporary state of tourism in Hawaiʻi is, in part, due to the state’s own historic definition of success.

The Aloha economy survives on tourism. Contributing 24.2 percent to Hawaiʻi’s total GDP and supporting roughly 229,000 jobs, the $18 billion industry is the state’s largest source of revenue and jobs. So the tourism bureau’s longstanding message to travelers —Do the islands. Tag your location at white sandy beaches and dramatic waterfalls. Explore Hawaiʻi’s hidden reaches.—isn't surprising.

Of course people listened.

But the state, critics argue, was measuring success in all the wrong ways: By how many tourists arrived and how much they spent. The metrics generated big dollars, but neither accounted for the real costs to the islands’ cultural and environmental heritage, or the lives of residents.

Hawaiʻi would have to find a way to prop up the tourism industry’s significant contribution to its GDP, while also minimizing its carbon footprint across the islands.

In 2020, the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority (HTA), the state organization tasked with overseeing the industry’s future vision and strategy, took the first step toward doing just that. Under a new Strategic Plan, the HTA traded the historic benchmarks of success for new ones: overall resident and visitor satisfaction, alongside average daily and total visitor spending.

Old Formula

Total Number Tourist Arrivals + Total Visitor Dollars Spent = Success

New Formula

Total Visitor Spending + Resident & Visitor Satisfaction = Success HTA would lean into tailoring Hawaiʻi’s economy around hosting fewer—but more engaged—tourists, with each willing to spend just a little bit more. In this way, HTA hoped the industry could make up its share of Hawaiʻi’s GDP, but out of the pockets of fewer visitors.

John De Fries, then-president and CEO of the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority, and his team arrived at this reimagined formula after consulting with the minds behind a burgeoning concept known as regenerative travel—Bill Reed, the father of U.S. LEED energy standards, Anna Pollock, the founder of Conscious.Travel, and the creators behind RegnerativeTravel.com.

Five principles underpinned this new paradigm of travel in their original whitepaper:

1. Whole Systems Thinking

2. Honoring Sense of Place

3. Community Inclusion and Partnership

4. Aspirational in Nature

5. Continual Co-Evolution

A proper regenerative travel strategy, the authors asserted, takes the local history, culture, and geography of a place into consideration, as well as visitor and resident well-being. In other words, it considers all aspects of the whole.

What if, the authors asked, instead of aspiring toward infinite growth, the tourism industry was leveraged to tap into the latent potential of not just the natural resources of a destination, but the latent potential of the collective cooperation and imagination of the local people and visitors of a place, too?

Where a “sustainability” framework uses benchmarks and metrics to monitor discrete parts of a system, the authors argued a “regenerative” one would focus on optimizing the potential of a system as a whole.

“The minute we start solving problems, we actually fragment the world,” Bill Reed says. By focusing on cultivating potential instead, he says, regenerative travel can help develop the capacity of all participants in a system—from individuals, businesses, and communities—to grow in their ability to organize and respond over time.

In practice, this looks like enriching the local ecology of a place alongside the education, health, and economic development of the local community. The more capability for cooperation, collaboration, and knowledge exchange in an ecosystem, the more resilient the system.

Drawing on this framework, De Fries and his team scoped out a new vision for tourism, one cementing the industry’s role to respect—and support—the flourishing of Hawaiʻi’s natural resources, culture, community, and economy.

Step Two: A new travel itinerary

The Hawaiʻi tourism industry had fed into the over-tourism of the islands for years, hosting extravagant press trips for travel writers in the early aughts that turned into glossy magazine articles, which trickled down to TripAdvisor top-10 lists and Instagram posts.

What if the HTA, De Fries wondered, could use that same soft power to nudge visitors to do good, rather than contribute to decay?

Enter the Mālama Hawai‘i campaign. Mālama is a Native Hawaiian word meaning ‘to care for’, as in ‘to care for’ the land, the sea, and future generations.

De Fries saw the potential to transform tourism into a tool to ensure Hawaiians have a vibrant home, strong community foundation, and quality of life for generations. Implementing this brand of travel became his top priority.

With the rollout of Mālama, HTA stopped marketing Hawaiʻi toward a “the-more-the-merrier” crowd, and instead sought to attract more “mindful tourists”—ones willing to give back to the islands and its people during their stays.

With Mālama, HTA designed and promoted a travel itinerary around opportunities for tourists to rebuild and repair, rather than degrade, Hawaiʻi’s ecology and culture.

How It Works

Tourists first encounter Mālama high above the Pacific Ocean. Educational videos in flight and pamphlets available upon arrival direct tourists to Mālama Hawai‘i, a website where 50 partner hotels offer free nights or discounted stays to guests who volunteer with participating nonprofits or community programs during their vacation.

The majority of volunteer opportunities are outdoors and regenerative in nature. Think: putting your hands in the earth—clearing invasive species to make space for new life, tending to a community garden—or pitching in for a weekly Surfrider Foundation beach clean-up. Other opportunities are more community or culture-based, like sorting food donations.

Yet some critics are concerned the Mālama campaign is just another brush of greenwashing—doing more to improve resident sentiment toward tourism on the islands than anything else. The campaign’s success, for instance, hinges on tourists seeking out regenerative activities for themselves, and hotels don’t have a way of tracking whether or not tourists follow through with their Mālama commitments. And, without statutory authority to enforce compliance of participating organizations, HTA lacks teeth to back Mālama up.

Meanwhile, more than 70 partner hotels initially agreed to participate in Mālama, but more than 20 have already dropped out, giving further fuel to critics: Were the hotels only interested in an initial blitz of publicity?

Still, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic.

Regenerative Travel Activities

On Oahu, marine biologist Dylan Brown, executive director of the Ocean Alliance Project, trains certified scuba divers to identify sea life, spot coral and turtle diseases, and otherwise evaluate reef health. He’s using tourism and citizen science to drive open-source data collection for the Division of Aquatic Resources. After each two-hour lecture, he takes divers to survey reef diseases. “We're using tourism to fund our database and monitoring ongoing threats to coral,” Brown explained.

Through Mālama, visitors are encouraged to partake in rich regenerative activities such as this one. It is just one of the dozens of volunteer and educational opportunities tourists are encouraged to partake in under the campaign. Other regenerative activities include invasive plant removal at Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, seed collection at the Waikōloa dryland forest to help replenish dwindling populations of native plants, and wetland habitat restoration to protect endangered birds.

While helping foster deeper and more respectful engagement with the island’s local history, culture, and ecology, providing visitors with enticing alternatives to lounging on the beach helps divert traffic away from strained tourist hotspots.

Still, the share of activities that meaningfully address the carbon emissions required to fly tourists to the archipelago are relatively few; visitors may volunteer to plant native plants or remove invasive pickleweed at ancient fishponds like Pearl Harbor, supporting the return of carbon-sequestering oysters.

Of course, Mālama’s aspiration of sustaining Hawaiʻi on fewer tourists should translate to a smaller carbon footprint, and while the other regenerative travel activities may not sequester carbon directly, proceeds from some, like Hawaiian Paddle Sports’ winter whale watching, do go toward conservation projects and other nature-based climate solutions.

Getting Cultural

A millennia ago, seafaring Polynesians followed the stars, currents, and migration patterns of birds over thousands of miles to first reach Hawaiʻi. Over time, they developed a rich agricultural tradition, cultivating hundreds of varieties of taro, sweet potatoes, and bananas from seeds brought across the vast Pacific.

This legacy continues today: local families have tended to heiau (ancient cultural sites) and taro patches for generations.

At Hāʻena State Park, a boardwalk constructed over one ancient taro field offers protection and a teaching moment. Visitors are invited to learn about Native Hawaiian culture, including the historical and continued significance of staples like taro; in 2018, this patch helped sustain residents in the weeks following an unexpected flood that left the only local road impassable.

Alongside the dilution of Native Hawaiian culture and tradition, Hawaiʻi’s tourism industry has long been critiqued for disproportionately excluding Native Hawaiians from enjoying the industry’s economic benefits. To help address these issues, other elements of HTA’s new strategy emphasize guiding tourists toward more cultural tourism experiences across the islands like this one.

By more actively promoting and fostering the islands’ art, history, nightlife, and music scenes, as well as cultivating the tourism workforce, HTA hopes to create more well-paying jobs and pathways into the tourism industry—providing residents and Native Hawaiians with lucrative opportunities that respect and elevate their history and culture.

Behind the soft power

The Mālama campaign’s tenents of developing regenerative travel and cultural tourism back up something bigger. Like the two halves of an intertwining strand of DNA, the HTA’s new marketing strategy is the soft power backing the hard power of concrete policy changes in Hawaiʻi. To reduce congestion and strain at some popular tourist hotspots, Hawaiian counties and state agencies have begun implementing advance reservation systems, paid parking, entrance fees, and shuttle transportation options. For instance, Hāʻena State Park implemented daily visitor caps and an advanced reservation system for non-residents, and parking permitting that prioritizes access for residents.

Hawaiʻi was one of the first states to ban plastic bags nearly a decade ago. In 2018, it became the first state to ban sunscreens known as toxic to reef life. Despite the ban, toxic sunscreens are still sold on store shelves just across the street from the beach.

A law signed by Gov. Green last June gives local community partnerships the right to manage state parks, as is already happening at Hāʻena State Park on Kauai. Residents now get to dictate how parking lot and concession stand proceeds benefit the park and their community.

And, in 2022, a federal initiative empowering “Indigenous communities to participate in national tourism goals and strategies” directed $1 million in funding toward Native Hawaiian organizations. Meanwhile, some state initiatives are supporting Native Hawaiian entrepreneurship and small business programs.

Short-term rentals are already banned in the majority of Honolulu.

Other policies contending with tourism’s true cost are still brewing, but not without resistance. In January of this year, Hawaiʻi Gov. Josh Green reintroduced a measure calling to implement a “climate impact” fee for visitors. Green estimated that the $25 fee could return $68 million annually that could be applied toward “prevention measures to help us avoid [other climate] tragedies like the one last year in Maui.” A similar proposal to levy a $50 fee was shot down last year.

The sum required to grapple with the industry’s true costs to natural resources is estimated at $360 million.

Bearing fruit

Formally rolled out in 2021, the seeds of Mālama Hawaiʻi have begun to flower. Accounting for inflation, overall tourism spending in Hawaiʻi was up 2.5 percent from September 2019 to September 2022. Tourists also spent more on daily activities, from hotels and tours to food and activities, according to NerdWallet, and guests extended the length of their stays. But the positive trend has begun to cool in 2024, as the economy slows.

But, according to Hawaiʻi’s Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, more than two-thirds of American and Canadian tourists at the start of 2022 participated in cultural and historical activities. That’s up from 55 percent of overall tourists in 2019.

Conclusion

Hawaiʻi is already one of the most cost-prohibitive travel destinations in the world, and the Mālama campaign and other climate-conscious efforts will likely only make it more so as the true costs of our impacts are factored into the price of travel.

Much of the Mālama campaign remains aspirational. For now, the campaign may label a new direction more than represent tangible changes to the industry. But, by shifting the focus from mass tourism to quality experiences that benefit visitors, residents, and the environment alike, Mālama just might be creating a space where a truly regenerative model of travel might actually be able to emerge, sketching a blueprint for others to follow.

Up Next

In the next dispatch, we’ll take a look at the “squishy” space between the hard and soft powers of implementing regenerative travel in Hawaiʻi, from the Aloha+ Challenge to community engagement, measuring impact and staying accountable, and fledgling attempts to redraw the supply chain.

Michele Bigley has written about regenerative travel for the New York Times, Conde Nast Traveler, Sierra, Toronto Star, and more. She is writing a book about parents facing climate angst with action. Follow her work by subscribing to her Substack.

As always, thank you to the readers, paying subscribers, and partners who believe in our mission. We couldn’t do this work without you.