The case for collective disaster preparedness

🔨 👷 🌱 🏙

Climate Solutions // ISSUE # 90 // HOTHOUSE 2.0

Hothouse is a newsletter catalyzing climate action edited by Cadence Bambenek. Additional editing contributed to this issue by Peter Gelling and Peter Guy Witzig.

Hello dear readers,

This last Saturday at 4 p.m. Central Standard Time, I stood outside in a sleeveless dress in 32-degree weather in northern Minnesota.

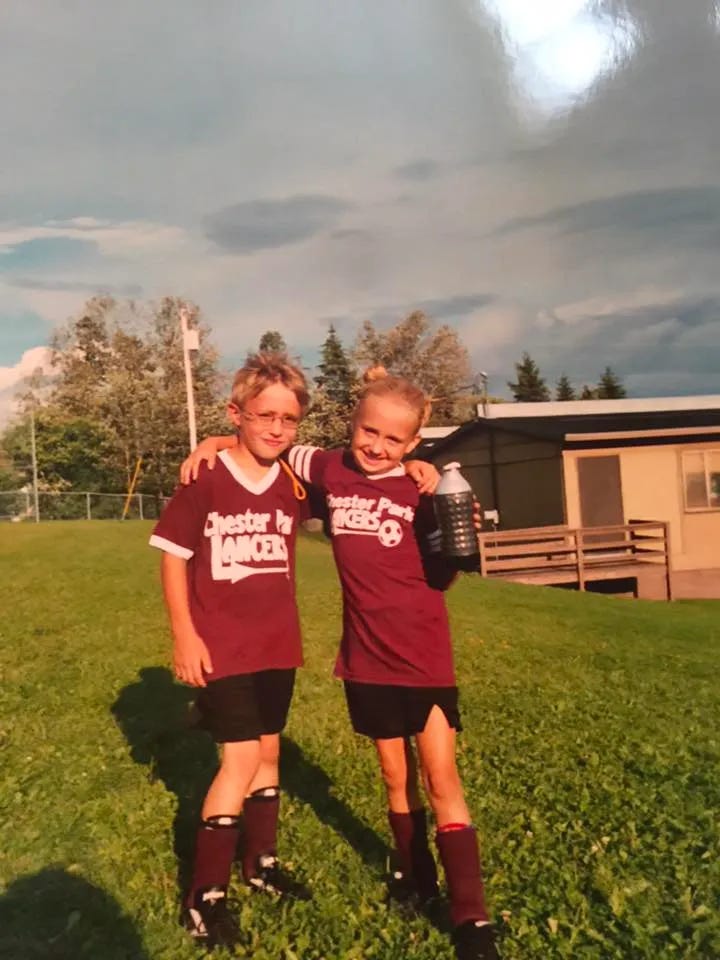

With snow falling on my shoulders and a bouquet of white roses and daisies quivering between my hands, my twin, Connor, and his new bride, Amy, read their wedding vows against a backdrop of a fallow field lined by poplar and pine trees.

I must admit, snow or not, it’s a surreal thing to watch your twin get married. After so many years of shared experiences, there’s a sense of finality that, here, the road truly diverges. At the same time, it felt beyond good to be surrounded again by the family, friends, and neighbors who helped shape my twin and me into the people we are today.

At one point during the wedding festivities, a family member happened to ask me where story ideas for Hothouse come from. It’s a good and relevant question.

While explaining to them the inception of this week’s piece, which takes a look at the role of community in adapting and responding to climate disasters, I realized this dispatch itself is the product of community-building.

Hothouse’s connection with today’s writer, the Los Angeles-based multimedia journalist Colleen Hagerty, was born out of the facilitation of a burgeoning community of independent newsrooms by the Local Independent Online News (LION) Publishers professional organization over the last couple of years: Hagerty and I met at a LION Publishers-hosted independent news sustainability conference (yes, it’s a thing!) last October in Austin, Texas.

Hagerty is an independent journalist on the disaster beat. As the Solutions Journalism Network put it, she has “reported extensively on policies, key players and impacted communities in this space for outlets including The New York Times, The Guardian, The Washington Post and Popular Science.” She also produces her own renowned newsletter on the matter called My World’s on Fire.

This month’s collaboration between Hothouse and My World’s on Fire, which plays on the strengths of each newsletter to produce an in-depth, practical, and engaging piece of work, is just one more reminder of the potential of community-building, be it online or IRL.

The same way it takes a village to raise a child (or a set of twins), it takes a village to foster and produce thoughtful climate journalism and to prepare for—and respond to—climate disasters.

Let’s take a look, and congrats to the new Mr. and Mrs. Bambenek.

❄️❄️❄️

Editor-in-Chief

The case for collective disaster preparedness

Doris Brown has spent a lot of time thinking about power. There’s power in the electrical sense, a subject that’s been top of mind for many Texans who have weathered blackouts and grid instability amidst extreme weather conditions in recent years. Then, there’s the power of weather itself, including the devastation Hurricane Harvey inflicted on her Northeast Houston neighborhood in 2017.

Researchers found the storm disproportionately impacted Northeast Houston; more residents reported damage to their homes than other parts of the state. For Brown, this statistic is personal. It’s the rushing water that poured through her ceiling, the wind and rain that dismantled the shelter she’d called home for 50 years. It wasn’t just unexpected, devastating, disastrous, and scary, she said, but an “invasion of privacy.” Hurricane Harvey left her home exposed, open to judgment by the parade of assessors and officials that followed.

Six years later, the damage from the storm is no longer discernible in Brown’s living room, but its impact lives on in other, less visible ways. It’s the reason why the power she concerns herself with most these days is the more ineffable sort; the kind that’s flexed in the creation of systems and societies.

Solace during systemic overwhelm

By the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s definition, large-scale or major disasters are a moment of systemic overwhelm, meaning that when disasters do occur, accessing aid during—and in the early aftermath—is likely to be challenging.

Other government agencies are more blunt about their limitations and the fact that help from officials might not be possible during or even in the days after disasters. As Crisanta Gonzalez of the Los Angeles Emergency Management Department told LAist in 2019, the city does not have enough first responders to help everyone if a major earthquake were to occur.

In other words: “We’re not coming,” she said.

So who is?

In Brown’s case, it was her neighbors, wading through water to reach her when Hurricane Harvey’s whipping winds and relentless rain drenched Northeast Houston, caving in her roof.

Her story speaks to a larger phenomenon of neighbors playing a key role in weathering worst-case scenarios. Neighbors are often a primary source of warnings before disaster strikes, offering the nudge needed to get you to evacuate or hunker down, depending on the risk. Then, in the crucial first hours of the aftermath, they’re likely to be the first people you encounter in your initial attempt to understand and address what just happened. They’re also likely to be the ones to help you re-establish your immediate physical safety.

In fact, studies have found that community connection is a reliable indicator of disaster resiliency.

“Social scientists have been able to demonstrate that communities with a high level of social capital, where people are connected to one another, recover more quickly and more completely after disasters,” seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones told The Los Angeles Times, going on to call community relationships the “most important” factor in earthquake preparedness.

FEMA also encourages personal disaster planning and administers free programming to train volunteers willing to perform disaster response tasks, such as basic first aid.

“The ability for…volunteers to perform these activities frees up professional responders to focus their efforts on more complex, essential, and critical tasks,” a FEMA webpage explains.

Neighbors pulling together in the thick of it can be seen time and time again in accounts from disasters across countries and throughout the decades, as Rebecca Solnit chronicled in her book, “A Paradise Built in Hell.”

With examples ranging from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, “when all the ordinary divides and patterns are shattered, people step up—not all, but the great preponderance—to become their brothers’ keepers,” Solnit wrote.

Call them grassroots initiatives, mutual aid movements, or simply good neighbors, as climate change dials up the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, such community-based post-disaster efforts are increasingly commonplace. And many are proving to have staying power, too, lasting long after the news crews and government aid dollars are gone.

Some of these networks borne out of disaster have become pillars of their rebuilding communities, able to shape not just the recovery process after a disaster but also the way future hazards impact their neighborhoods. And, for many communities adapting to the changing climate, that next time is all too soon.

Phase One

For Lauren Kruz, the reality of “we’re not coming” set in this past winter when historic storms dropped more than 100 inches of snow in a matter of days onto her community in the San Bernardino Mountains of Southern California. The deluge limited access in and out of several mountain towns, meaning officials and first responders were not able to reach residents right away. “It shut our whole community down,” Kruz, who lives in Twin Peaks, recalls. When plows finally did come through, their carved-out paths created thick walls of snow in front of houses, trapping some people on their own property. In early March, officials reported 13 deaths in the impacted area.

For some residents, the threat was immediate—roofs collapsed or were otherwise damaged; buildings lost power, leaving people more vulnerable to the cold. For others, the concerns compounded over time as they were unable to address medical needs or access food.

“Our main grocery store, a couple days into the storm, their entire roof caved in, and our other grocery store also closed down, red tagged for various problems as well,” Kruz said. “So there was no place to get food for several weeks.”

Kruz is a founding member of the Mountain Provisions Cooperative, an accessible food initiative that had yet to launch when the snow started to fall. Kruz and her fellow members quickly realized that the same sort of food security issues they formed to address were only going to be heightened during the storm, so they created a Google form for people to share their needs and circulated it in local Facebook groups. They received more than 400 responses, including requests for items like food, diapers, and medicine.

From there, the cooperative was able to act as matchmakers between those who had extra supplies and those in need. At the same time, they began coordinating with people outside the area to bring in groceries, facilitating food distribution sites and a free pop-up shop with necessities.

External aid eventually arrived in multiple forms, from helicopter food drops and GoFundMe donations to a federal disaster declaration, which allowed impacted residents to apply for FEMA aid. But Kruz said the storm led her to recognize her community had “stones that were left unturned,” like the significant income inequality between resort and residential areas in the region.

Extreme weather disasters have a way of slamming the breaks on everyday life and forcing attention on structural issues that have often been simmering at or just under the surface. With daily life suspended, survivors often note the opportunity for new connections and even new ways of approaching these longstanding issues.

Beyond isolated incidents

On a warm fall day last year, the hot Texas sun beating into the red curtains of her living room, Doris Brown sat under the spot where her roof had caved in and spoke to the systemic hurdles she encountered after Hurricane Harvey. Six years on, there are still noticeably damaged houses in Brown’s neighborhood, which is considered a lower-income area and has a majority-minority population. By contrast, nearly 82% of Houston residents overall reported being “completely or mostly recovered” from the effects of Hurricane Harvey in a survey conducted last year.

Just like power, disaster recovery can be ineffable, a process that includes plenty of benchmarks but no clear ending. In a community like Brown’s, there’s the question of what it even means to recover when the status quo was already failing to meet residents’ needs.

“We never seem to recover at the same rate as everybody else, because we have historically been disinvested out here,” Brown said. “There were already barriers, and when [officials] came to the neighborhood, they came with the barriers.”

For Harvey-impacted residents, those barriers included lengthy applications for state and federal aid, some of which required extensive documentation or even a credit check.

FEMA ultimately denied Brown’s application, so she once again turned to her community for help. A local reverend connected her with an informal group of Houston residents that called themselves West Street Recovery. Recognizing the unmet needs in areas like Northeast Houston, the volunteer-run effort began helping muck out houses and do basic repairs, an offer they extended to Brown. As of this year, the group has performed similar services for more than 300 homes while expanding its offerings to address the additional disasters Houston has dealt with in the years since.

“We came about in the aftermath of Harvey, then we responded to [Tropical Storm] Imelda a couple of years later, then we responded to Covid, then we responded to the Winter Storm Uri,” Alice Liu, West Street Recovery’s Co-Director of Communications, Rebuild, and Fundraising, said. “None of that would have been possible if we had just treated Harvey like an isolated incident.”

Today, Brown’s garage is equipped with supplies including a power station, inflatable raft, food, water, and a waterproof “go bag” with hygiene and medical items. Her home has been transformed into one of West Street Recovery’s first “hub houses,” a designated spot for neighbors to gather at or borrow supplies from in case of disaster.

It’s not to say more roofs won’t be damaged come hurricane season, but that, if they are, neighbors now know to head to Brown’s for help.

Over the years, West Street volunteers have become experts in things like generator safety, home repair, and drain maintenance. Still, members came to realize that there were some challenges beyond the capacity of individual households left to address.

For example, Brown’s neighborhood has an open ditch drainage system, which was poorly maintained and led to regular flooding, even during unnamed storms. So, Brown began speaking with her neighbors, and they formed their own advocacy group called the Northeast Action Collective, or NAC. They won research grants to investigate their neighborhood’s drainage problem and potential solutions, and with the support of West Street Recovery, Brown and some of her neighbors began testifying week after week in city council meetings about the problematic drainage.

This summer, after years of NAC members holding meetings, hosting rallies, and giving those testimonies, the city council voted to increase funding for drain maintenance, and the mayor announced the city would take over open ditch maintenance. With these changes, NAC members believe they will see less flooding from future storms.

But other barriers remain. In 2021, the group partnered with non-profit Texas Housers to file a federal discrimination complaint claiming the state’s General Land Office “violated the civil rights of Black and Hispanic Texans” through its distribution of federal disaster mitigation funds, which the complaint alleges were distributed using a formula that “substantially and predictably disadvantaged Black and Hispanic residents.” This case is still underway with the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Through these campaigns and other activities, Brown and her neighbors are collectively changing the way their community will experience future storms, as well as working to address the systemic issues and bureaucratic hurdles disaster survivors often encounter during the recovery process.

“We're not sitting back while people sit up in those ivory towers and look at data that's 10 or 15 years old and then want to come back and tell us what we need,” Brown said. “We realized that we are the experts of what's going on in our neighborhoods.”

The first step

Being the experts of their own neighborhoods means Brown and Kruz recognize the specific risks, needs, and resources within their communities. What worked for Brown’s community might not work for Kruz’s or vice versa, but their experiences offer examples of how grassroots organizing can evolve to address issues beyond the initial needs of recovery. They also exemplify the benefits of integrating a community-grounded approach as part of the larger United States disaster response landscape.

Of course, there are limitations as to what grassroots groups can accomplish, particularly as members reckon with the effects of disasters when they do hit home. The experience of being a disaster survivor carries a significant weight itself. This collective-response model offers an opportunity to share that burden, but the recovery can still be exhausting, the advocacy time-consuming, and the related costs often far surpass the coffers most community groups have on hand.

Ultimately, institutional aid remains critical for addressing large-scale disasters, providing significant financial support and expediting the recovery process. But groups like the NAC are showing the cracks in these systems, and experts and politicians alike have begun calling for significant changes to how we prepare for and respond to disasters in recent years. Some are calling for an increased focus on assisting historically disadvantaged communities like Northeast Houston, whether that’s through funding mitigation projects or adjusting application requirements for federal aid. There are also ongoing discussions in Congress about the role of the FEMA in these unpredictable, climate-changing times.

“I think disaster recovery and disaster preparedness hasn't been fully integrated enough into the climate action conversation,” Liu of West Street said. “How can we rebuild in a way that isn't just building back to the status quo, but is actually able to coordinate communities towards resilience and address some of these historic inequities?”

These sorts of changes happen slowly, though, negotiated in the halls of Washington DC and other “ivory towers,” as Brown put it. Coalitions of survivors can provide not just a model for collective response, then, but a mechanism of pressure, keeping their communities in the news and on the radars of their representatives.

In the meantime, residents in disaster-impacted communities continue doing what they’ve always done. In Vermont, thousands coordinated aid on an online forum after historic floods this summer. When Lahaina residents needed supplies in the early days after the deadly Maui wildfire, it was locals—primarily Native Hawaiians—who came through with boatloads of necessities.

By the time you read this, there are likely to be even more recent examples that come to mind. The disasters might be different, but often, Brown believes, the community responses begin with the same first step: someone having the strength to speak up.

More on how to do that in your own neighborhood in the next edition of this two-part series.