The average household spends $1,800 per year on food they throw out

People in richer countries are more likely to waste food, despite rising demand for food banks

Simple climate action at home // I S S U E 2 // F O O D W A S T E

Last week we introduced you to the world’s food waste problem. This week, we’re inviting you to try our Hothouse Challenge: Can you cut your food waste by half or more for one week?

The average family in America wastes an astounding 2,425 pounds (1,100kg) of food every year, roughly the equivalent by weight of buying almost 10,000 quarter-pound burger patties and throwing every single one in the trash. In climate terms, it’s the equivalent of taking a weekly 85-mile car journey.

As we explore in this week’s feature on “community fridges,” people in more affluent countries waste more food despite rising demand for food banks across the US and UK.

Why do we waste food? A few bad habits from a lack of planning before shopping to how we cook. So our challenge to you this month is to reduce your household food waste by at least half.

The challenge begins with simple practical tips. Then we move on to bigger steps. Pick the ones that feel realistic for you; a couple of easy things if you’re busy, all of them if you’re feeling ambitious. To keep this top of mind, we’ve made you a Hothouse Challenge poster that summarizes all our tips. Print it out and put it on your fridge, share on social, or save it on your phone.

The Hothouse Food Waste Challenge

Last week, we invited you to note how much food waste you created during a typical week. (Or start now - it’s not too late!)

For week two, follow our tips for reducing food waste, and record your food waste again. Next week, we’ll ask you to compare both weeks and send us your results.

Basic tips

• Buy the fresh food you’re most likely to eat. Topping up is better than one blowout shop.

• Order the food you’ll eat when dining out. Will you really eat the leftovers the next day?

• Store food in glass or clear containers so you can see what needs eating.

• Ignore best before dates. Your nose knows what’s still good!

Plan a few meals for the week

Sketch out what you need for a few days worth of breakfasts, lunches, and dinners. Check what food you already have, then write your shopping list. Don’t be tempted by special offers in-store — buy what you need. Online meal planners can get you started.

Organize your fridge

Different foods last longer in different parts of the fridge. Use the veg drawer, and remind yourself what should be stored in the fridge and where.

Make the most of your freezer

Buy frozen veg and freeze food you can’t eat in time. You can freeze most foods, including fresh herbs, avocado and bread. If you have a veggie stockpile, blanche it and freeze for handy evening greens.

Explore leftovers recipes

Check for leftovers or food that needs eating before you start cooking. Soups, stir-fries, sauces, and smoothies are great for using up veg. Type ingredients into Google for recipe suggestions, or use a leftovers cookbook.

Avoid landfill

Think of your food waste in three types: good food that just didn’t get eaten; scraps you don’t use (such as onion ends and broccoli stems); and waste you can’t eat (like avocado skins and teabags). The worst option for any of this is landfill, because food that ends up there releases methane, a greenhouse gas 35 times more potent than CO2. Instead, compost in your garden, your apartment, or, if you have access to one, use your household green bin. For food scraps, there are dozens of ingenious solutions, including freezing veg offcuts to use for soup stock, and regrowing onions from the root ends.

That’s it! Enjoy it, and make notes of what you find helpful and what’s hard. Reply to this email to send us feedback. If you’d like to share your progress, find us on Facebook or Instagram. #hothousechallenge

Illustration by Jago Silver

Challenge Diary: Reducing our Food Waste

By Jemima Kiss

I knew most of those tips for avoiding food waste, but it’s different trying to live them every day. Recording our food waste last week highlighted some embarrassing overbuying and disorganization. So this week we made more effort to eat our leftovers, and made a game out of using up what was in the fridge. We gave the kids smaller portions, and used things up in sauces and soups. Consequently, I cooked some really weird meals: leftover pasta fried with bean sprouts, roasted beetroot, and veggie bacon, and soup made with squash, green lentils, beetroot juice, and tinned sweetcorn. If I invite you to dinner, politely refuse.

On the plus side, I turned a very stale bagel into delicious croutons, made tasty smoothies for breakfast using rubbery things from our fruit bowl, and managed to go the entire week without buying any new food. Some of our food waste is stuff we can’t eat, but that goes in our compost bin. After a week, we’d cut our waste to 7lbs, or 3 kg, just a quarter of what we wasted the week before. Now we just need to try and stick to our new regime.

The luxury of food waste

Community fridges were set up by environmentalists to prevent food waste, but have become a lifeline for people too poor to waste food

By Thomas McMullan

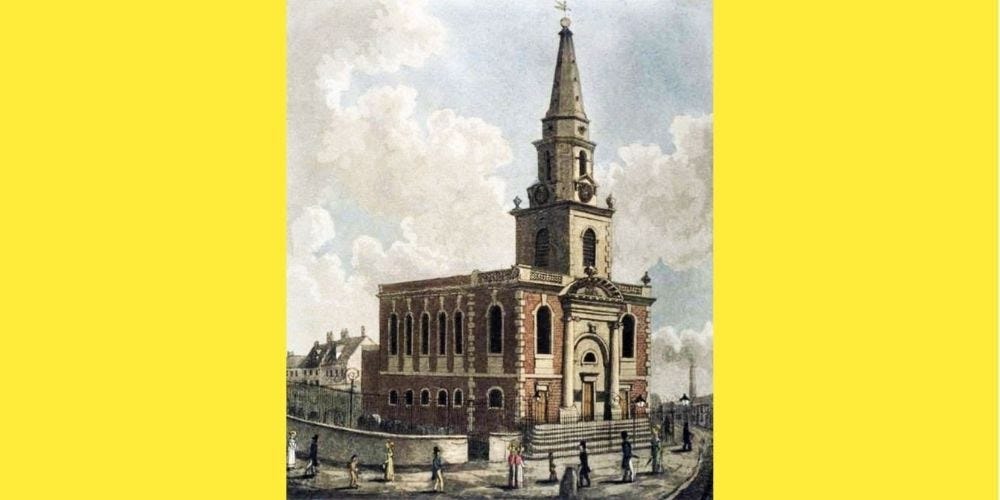

St George the Martyr is a handsome, red-brick church with an imposing white spire, and stands in one of the oldest parts of London. Historically, it’s also one of the poorest, with centuries-old sites of executions, prisons, and slums. Charles Dickens lived nearby as a child. His father was once kept in the Marshalsea debtors’ prison that neighbored the church, and the neighborhood is haunted by “the crowded ghosts of many miserable years,” as the writer would describe it in the preface to Little Dorrit.

St George the Martyr Church, Southwark, London

Today, St George the Martyr is surrounded by the noise and bustle of Borough Market, by upmarket cafés and restaurants. But the church still borders some of the city's impoverished neighborhoods. Up until recently, if you scaled the stone stairs to the church’s side entrance on a Tuesday afternoon, you’d find a supply of free food. Tucked in a cozy porch, along with a kitchenette, a freezer, and a large fridge with a glass door, you’d find fruit, vegetables, milk, bread, and meat. And for a few hours each week, the room would be open to anyone and everyone.

‘Coffee shops were closing and throwing 200 liters of milk down the sink’

Opened in 2019, the community fridge took unsold food from nearby businesses and made it available to anyone who might need it. Up to 20 people would call in on Tuesdays. Some were homeless, others looking to bolster a weekly shop with a few free essentials. Most were struggling with hunger. Positioned between tourist-friendly markets and social housing, between food surplus and food poverty, the community fridge project had real value. For several months, volunteers redistributed produce that would otherwise have gone to waste.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic hit. “There was panic in supermarkets, and things started to go out of stock… coupled with lots of businesses being in trouble, including cafés and restaurants,” says Kate Sing’ombe, who runs the community fridge. “People were unable to buy milk in supermarkets, but we knew coffee shops were closing and throwing 200 liters of milk down the sink. We went into overdrive and started hoovering up as much surplus food as we could across London, from local cafés to Harrods Food Hall. We took two vans of duck eggs.”

As London lurched into lockdown, Sing’ombe’s operation tried to get as much food into circulation as possible. The number of people turning up swelled from 20 to more than 100. At one point, when the entrance hall wasn’t big enough to hold the food, the whole back end of the church was filled with produce saved from closing businesses. Then, when social distancing measures came into full effect, the project began to struggle with both demand and safety regulations. The church was forced to close, along with the fridge, and switched to a delivery model to feed the most vulnerable.

Food accounts for up to 37% of emissions

The idea of a community fridge is simple: if you are hungry, you can take away something that would otherwise have been thrown away by a supermarket or café. The reality is often more complicated, with limited opening times and a reliance on volunteers, but the principle is that surplus food can be taken by anyone.

The concept was started by environmentalists. It has spread across Europe over the past decade, the UK following the lead from Spain and Germany, where ‘solidarity fridges’ started in 2012. Organizations such as Foodsharing.de started to use communal fridges as a way to draw attention to the scale of the food waste problem in our cities. Initiatives now exist in the United Arab Emirates and India as well. The US-based community group Freedge, which is building a database of every community fridge in the world, has several hundred projects registered.

From an environmental perspective, the impact of food waste is staggering. Agricultural production, supply chains and food consumption represent 21% to 37% of all human-generated greenhouse gas emissions, according to research published in Nature Food in February 2020. Yet globally, an estimated 30% to 40% of all food produced is wasted.

Against this backdrop, food sharing has grown into a worldwide phenomenon. On the spectrum of food-sharing initiatives, community fridges sit somewhere between micro-scale projects like Casserole Clubs, which encourage neighbors to share spare portions of home-cooked meals, and projects that aim to recover surplus food higher up the chain, such as Boulder Food Rescue in the US, or FareShare and Hubbub in the UK.

Hubbub’s community fridge in Milton Keynes, UK

However, unlike food banks or other emergency facilities aimed at alleviating food poverty, these community fridges don’t require government approval to use. “You don't need a referral process and you can use them as many times as you like, so if you live nearby you can just come and use the fridge,” says Kanahaya Alam, community fridge network manager for Hubbub, which supports close to 100 community fridge projects across the UK. Alam says the network has grown rapidly since the first fridge was set up in 2016 as part of a partnership with the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s.

The communal space is important, she says. On a practical level, there have to be people that clean and look after the fridge. In many places, the fridges are staffed by volunteers and only open during certain hours. With these measures in place, people visiting the fridge tend to be respectful of sharing, taking a bag of oranges and a pot of yogurt instead of treating it like a free supermarket. Alam notes that some projects also run cooking or budgeting workshops, becoming places people can go to socialize, learn new skills or try new food. “We always talk about fridges as something that foster community spirit rather than solving food poverty and food waste, which are two different issues,” Alam told Hothouse. “One shouldn't necessarily be the solution to the other.”

But food sharing finds itself positioned between two of society’s biggest ills: hunger and food waste. Even in wealthy nations such as America, some 37 million struggle with food poverty, yet still at least one-third of food goes to waste. Community fridges, while small in scale, address both issues.

“The beauty of the community fridge is that it can be all things to all people,” says Steve Hedger, who runs a community fridge at the Albrighton Community Center in Camberwell, one of London’s most deprived areas. “Hubbub and the supermarkets came at it from a reducing wastage point of view and that is undeniably what it does, but the reason that people come to it — the takers rather than the givers — is because they need food. In doing so, they are in effect doing their bit to help the environment and reduce wastage as well, but that's not the primary reason.”

The drive for food equality

The community fridge is a hopeful model, inherently trustful in people’s ability to share, but it has been pushed to its limit by the Covid-19 pandemic. With its church doors closed, St George the Martyr has been forced to move to a delivery model. The fridge’s environmental impetus has been overtaken by its humanitarian one. It’s a shift that many community fridges have made.

A volunteer hands out food at Hubbub’s community fridge in Leytonstone, London, UK

In Swansea, Wales, where pre-packaged parcels are now served through a window on the side of the building, the messaging has been changed to target those in most need, rather than those who would use the fridge primarily for environmental reasons. “There are a lot of people now, because of a change in their financial circumstances, who don't have access to food, who have no means to pay for food anymore,” says Hedger. “We are becoming their sole source of food, but we weren't ever intended to be that. One of my concerns is that the consequences if we don't have food are much more serious now.”

What does a long-term solution to food equality look like? And should we continue to rely on charities and volunteers to salvage some of the food wasted on an industrial scale — even as people living in the next street are struggling to afford to eat? Community fridges hint at what’s possible. But ultimately, the world will need to rethink how we get our food from farm to fork. The world can’t reach its environmental, or humanitarian goals, without tackling the reality that at least one-third of food grown every year is never eaten.

Back in St George the Martyr, there is a stained-glass window featuring Charles Dickens’ Little Dorrit. The church had become a refuge for the young girl whose father is imprisoned in debtors’ jail next door. Like so many other Dickens characters, she knows how swiftly our fortunes rise and fall. Charity can save lives, but Dickens’ books also show us that what a broken system really needs is reform.

Hothouse is a weekly climate action newsletter written and edited by Jemima Kiss, Mike Coren, and Jim Giles. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read.