Eating bivalves—even better for the climate than going vegan?

Why a new generation of farmers is turning to the sea

Simple climate action // I S S U E # 5 2 // S E A F O O D

Hothouse is original journalism about climate solutions in your own life. Sign up today.

Here comes the protein transition

Our future is what we eat

I suspect you’ll hear a lot more about bivalves in the coming years. They’ve gotten short shrift over the last century. Eclipsed by the craving for ahi tuna and snowy filets of Chilean sea bass, the lowly oyster and its mollusk cousins have not gotten their due.

In their day, oysters were as American as apple pie. Mark Twain, the author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, raved about them, along with millions of Americans, from the working class up to the robber barons. Twain indulged a personal taste for the tiny, coppery Olympian oysters which still grow along the Pacific coast today. They once arrived on America’s plates in every way imaginable: tins, BBQ’d, half shell, or fresh, for anyone willing to wade into the mudflats surrounding America’s big cities.

The bivalve’s time has come again.

Just as humanity has embarked on an energy transition—weaning itself off fossil fuels—we’re now entering a protein transition as well. Agriculture represents a quarter of humanity’s GHG emissions. Left unchecked, our food supply’s emissions will dominate global emissions by 2050. Most come from cattle and livestock.

In the next century, we may grow just as much “meat” as before, but what we grow (and where it comes from) will look very different. Plants, labs, and… shells? That’s what this month’s all about: ocean farming. We’re not just exploring the idea, but two big experiments—small vertical farms on the eastern coast of the US and massive pens taking shape on the West Coast—pointing the way toward a very different future for seafood, and for us.

Mike Coren

Editor-in-Chief

mj@hothouse.solutions

How many times a month do you enjoy seafood? 🍣 🐟 🍥

Bivalve revolution

By Maria Finn

In coastal towns around the world, fish are the calendar, the currency, and the food. Life’s rhythms and meaning are shaped by what swims beneath the surface. So it’s easy to assume that fishing is what’s destroying our oceans. And in some cases—like the free-for-all on the South China Sea—that’s true.

But on a global scale, the problem is really industrialization. It’s fishing as mining, not farming or harvesting. Any fleet can overfish. Extracting huge amounts of one species from the ocean, or even large-scale monoculture ocean farms, decimates biodiversity, triggering a cascade of environmental and social problems. See (some) shrimp ponds in Thailand and salmon farms in Chile.

But the opposite is also true. When done right, farms, and fisheries, can restore ecosystems (see RARE’s Fish Forever program allowing millions of small fishers to boost catches by managing their own marine reserves). And nobody wants fisheries to thrive more than the families that have subsisted on them for generations, whether they live in Kodiak, Alaska, or Puntas de Choros, Chile.

Just as there’s a small but growing movement of regenerative farming on land, there’s now a burgeoning movement at sea.

Today, the world’s oceans and lakes give us 17% (and growing) of the world’s protein supply while serving as the primary sustenance for at least 3 billion people. But they aren’t infinite. As global catches began to stagnate in the early 1990s, global consumption skyrocketed. Farms met almost all that demand. Over the last two decades, reports the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, fish farming has risen 50-fold. It shows no signs of slowing.

We can choose to eat in a way that supports our coastal ecosystems, or destroys them. If they (and we) are going to thrive, it will mean reinventing farms to regenerate the ocean during an era of extreme climate change.

For that, we need to reintroduce ourselves to the bivalve.

Freedom oysters

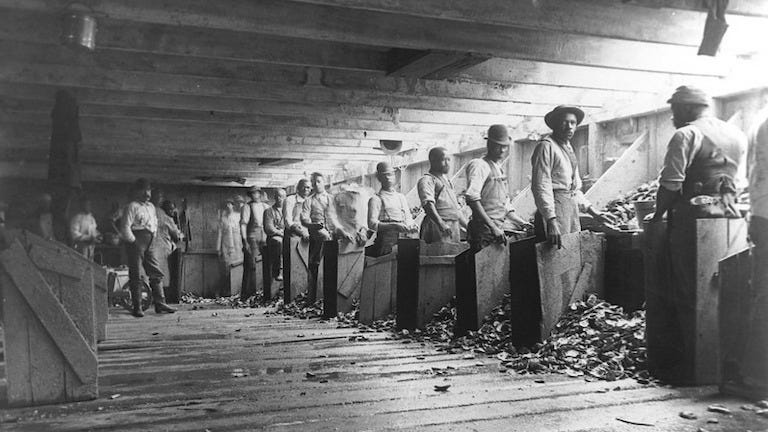

In the 1800s, America’s oyster carts were as ubiquitous as today’s hot dog stands. It was America’s most common and beloved source of protein. Oyster houses and saloons proliferated. High-end restaurants in New York City featured dishes like scalloped oysters and oyster-stuffed chickens. They were cheap, plentiful, delicious and nutritious.

The story of America could be told by the homely bivalve. Massive middens, or oyster shell and clam shell mounds along the Chesapeake and San Francisco Bay are evidence of indigenous people’s fondness for these and other shellfish of the intertidal zone, like clams, mussels, and scallops. New York Harbor and San Francisco Bay were rich with shellfish and reefs. In 1609, when Henry Hudson arrived in New York City, there were about 350 square miles of oyster reefs. This natural bounty meant deeply contoured intertidal zones that provided habitat for numerous sea creatures. Waters teemed with fish.

The rise of the railroad meant oysters could be shipped live in barrels filled with seawater, and tinned oysters became popular as well, omnipresent in the diet of residents of coastal cities and inland settlements alike, according to the book Down by the Bay by Matthew Morse Booker. During his San Francisco days, author Mark Twain rhapsodized about his oyster intake. After downing oysters for breakfast and lunch, Twain wrote in 1864 he felt compelled “to move upon the supper works and destroy oysters done up in all kinds of seductive styles.”

Historically, these were wild oysters being eaten at low tide meant residents could forage the tideline for seaweed and shellfish. Oysters filtered their water, feeding on naturally occurring algae, giving plankton and eelgrass more sunlight, while improving water quality. But too many oysters were taken from the bays of New York, silt and toxins from gold miners in California destroyed the oysters in San Francisco Bay. Sewage-wise, a lot has changed about the water quality around urban areas since the 1800’s.

Today, oysters have all but disappeared from the bays. Burgers and hot dogs replaced them on our plates. This isn’t just a culinary loss. Wild oyster reefs contoured the bottoms of the bay, which helped mitigate storm surges and sea-level rise. Hurricane Sandy cost an estimated $70 billion, mostly from flooding. A University of Massachusetts study found that with no oyster beds present, the wave energy in New York City harbors is 200% higher. In San Francisco Bay, oysters used to fringe miles of living shoreline, 98% of which are gone. The region is facing an estimated $100 billion to mitigate sea-level rise.

Yet shellfish have a remarkable quality: they are regenerative. The more we farm, the better their (and our) environment gets. These intrepid filter feeders engineer their ecosystems to the benefit of others from seaweeds to fish spawn. Bi-valves are powerhouse carbon collectors as well. Shellfish colonies are considered “Blue carbon” ecosystems as they extract carbon from the water to grow their shells Along with ecosystems like wetlands and mangroves. This carbon is permanently removed from the ocean.

Can we apply this regenerative principle to all of humanity’s seafood? Two experiments—a cadre of small, sea-steading farmers on the East Coast and massive, technologically advanced pens on the West Coast—promise to do this at scale. Each one, in vastly different ways, is testing the proposition that we can feed the world with the oceans without destroying them.

Seawater is the new soil

Imagine a lone boat on a fog-capped, rocky bay, a steady hum of hydraulics as lines are pulled from the ocean festooned with kelp, rich in nutrients and protein, that grows up to 12 feet long in a few months. To do this, it pulls huge amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. It’s also used in biodiesel and as a fertilizer. Alongside the kelp, a raw bar weighs down the buoys: oysters, clams, scallops, and mussels. With just one acre of these saltwater farmsteads, claims GreenWave, a startup dedicated to regenerative ocean farming, you can grow 30 tons of seaweed and a quarter of a million shellfish per acre.

GreenWave has received a lot of buzz. The organization’s mission is “to restore marine ecosystems by creating 3D ocean farms that provide habitats for thousands of fish, filter the water of deadly carbon and nitrogen, and grow tons of sustainable shellfish and sea plants.” From features in the New Yorker to The Atlantic, many are holding out hope that these mom-and-pop micro-farms are seen as a possible solution to our seafood maladies.

Co-founded by former commercial cod fisherman Bren Smith, the idea is to create small ocean farms—about an acre in size each—that use every inch between the surface and seafloor for growing food, fuel, and sequestering carbon. Long ropes and cages host a complementary menagerie of species, including kelp, mussels, oysters, scallops and other bivalves. Imagine a marine barnyard of biological and economically diverse crops. The goal is that with as little as $20,000, a one-acre vertical farm can start producing food in the Long Island Sound or Maine’s coastal inlets.

So far, yields from GreenWave’s 140 farms from Connecticut to Alaska amount to a tiny fraction of the 10 billion pounds or so of seafood the US lands each year. But the small non-profit can’t keep up with demand from would-be aquafarmers: a backlog of 8,000 people have inquired about starting their own ocean farms. GreenWave has set the goal of helping launch 10,000 vertical farms in the next 10 years. The upstart is creating online resources like instructional videos and how to fill out permitting papers to meet the growing demand from small start-ups.

A Pacific twist

On the other side of the country, the Catalina Sea Ranch took an entirely different approach. Anchored miles offshore not far from Los Angeles, it sought to turn the cold, deep waters of the Pacific into a new agricultural frontier. Punishing conditions off California’s coast make small aquaculture farms extremely difficult and expensive. So like salmon farms in Norway, Catalina Sea Ranch was forced to go big.

When Catalina Sea Ranch pioneered a bivalve farm in federal waters six miles off Huntington Beach, it was no mom-and-pop operation. They raised $5 million to create a 100-acre mussel farm, with plans for rapid expansion to 3,000 acres. They partnered with Verizon for real-time automated monitoring “smart buoy.” The business plans called for growing abalone, lobster, oysters, clams, and seaweed. They also teamed up with the University of California, Irvine’s Department of Molecular and Computational Biological Sciences to breed super mollusks that reproduce prolifically, grow quickly, and have a greater Omega-3 content. To get ahead of an increasingly acidic ocean’s destruction of mussel and oyster seed spat, they hired biologists for cryopreservation research to create ideal larvae that can withstand ocean acidification for Pacific Coast shellfish farmers.

Catalina Sea Ranch was ambitious, scientific, and data-driven, and well funded. It was also bankrupt by 2020. The founder, Phil Cruver blamed the onerous bureaucracy of the federal government for the failure and “heightened requirements” around doing business in federal waters. While CSR said it had the capacity to sell 2 million pounds of mussels a year, data published by Undercurrent News showed “they sold 65,440 lbs of mussels over their lifetime or just 3% of its annual target.”

Things only got worse in 2019. A broken line from CSR wrapped around the prop of a boat, capsizing it. A passenger, 71-year-old Maynard Poynter, drowned. His family sued the farm for $10 million. By 2020, CSR had sold its assets, casting a shadow on the future of large-scale, offshore aquaculture.

These appear to be cautionary tales about farming the oceans: either too small to matter, or too expensive to succeed. But they’re likely only growing pains.

Aquaculture is going to expand in the United States. Plans are underway, for example, on the California coast near Ventura to farm 2,000 acres of mussels. Seeded by a grant from NOAA in 2015, the goal is for 20 plots of 100 acres each of Mediterranean mussels in the Santa Barbara Channel Ventura Harbor. Ventura Shellfish Enterprise intends to bring together a collective of seafarmers to operate their own plots while handling elements of the business too onerous for a single operation like permitting, monitoring, and marketing.

Next week we’ll explore how a new generation of farmers are turning to the sea, and what may end up on your plate in the next few years.

Hothouse is a weekly climate action newsletter written and edited by Jemima Kiss, Mike Coren, and Cadence Bambenek. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read. Like what you’re reading? Share Hothouse with a friend!

Love Maria's writing!