Covid’s plastic pandemic

It’s harder than ever to fight single-use plastics, but change is coming.

Simple climate action at home // I S S U E 6 // P L A S T I C S

Fighting back against plastic — and Covid-19

By Jemima Kiss

For the past two years, our grocery shopping routine has involved a trip to the bulk section in our local health food store. We make a note of all the dry goods we need — sultanas, flour, chocolate chips, pasta, red lentils, oats, noodles — and take glass jars to fill up. Most bulk food costs significantly less than packaged food: pasta $2.99 per lb, a jar of ground coriander for 51 cents, 3-cups of instant yeast for $7. Then we buy a round of fresh produce at a modest local store.

Each month, we’ve been saving a couple of hundred dollars over the supermarket. And until Covid hit, we were almost completely avoiding plastic packaging.

Covid has created a perfect storm for producing plastic waste. Millions of non-recyclable masks, shields, and gloves are ending up in landfill, or the sea. The drop in oil prices means it’s far cheaper for those to be made from virgin plastic than from recycled. Disruption in transportation and shipping means that many recyclers and waste pickers are at risk of bankruptcy.

It’s been a huge blow to citizens who’ve been trying to cut down on plastic use as part of the fight against climate change. Here in the Bay Area, we’re still able to buy in bulk at our local store, but some bulk stations have been replaced with pre-packaged plastic boxes. Most cafes refuse to fill reusable cups, even though the chance of Covid-19 transmission from surfaces is very small.

For the moment, our plastic-free shopping trips are harder. We’ve just had to seek out the cafes and shops that do still allow the use of personal bags and keep cups, with precautions. We make sure our reusables are clean. We can put our reusable cup on the counter, and the barista can fill it without touching it. We can use our own shopping bags, but keep them in the cart rather than loading the packing area.

Eventually, this chapter will be over, and we’ll all go back to a healthier routine — even though the plastic created by this nightmare will live on for several hundred years longer. But saving and documenting our family’s plastic waste revealed how much of it can enter our house, and the landfill, if we let it. By making it more visible, we feel more committed to doing something about it. We’re not the only ones. This week we meet Jeff Kirschner, who explains how picking up litter during a walk near their home in Oakland sparked a global movement.

Read past issues on our site. Send us feedback. And please share this newsletter. Thank you for reading.

Illustration by Jago Silver

The Hothouse Challenge: Paring back plastic

Last week, we invited you to save all your plastic waste, and take a photo of your stash at the end of the week. This week, we’ll cut back with the tips below. Next week, measure your plastic waste again, compare and send us your results.

Step One: Food Shopping

Food shopping is by far the biggest source of plastic waste in your home. The easiest ways to cut back are:

• Take your own bags. (Make sure they’re clean, and keep them off the checkout.)

• Avoid pre-packaged fruits and veg. Buy or make smaller, reusable produce bags.

Crash guide to buying in bulk

• You’ll need clear, reusable jars, scales, and a Sharpie. Start with two or three to see how it works.

• Find your local bulk store. Try your local health food stores, or Whole Foods.

• Before you go, list what you need and find jars for everything.

• Weigh the empty jars, and write the weight on them. (This is your ‘tare’ - they’ll take this off the final weight when you pay.)

• Fill them up, and write the product code on each one next to the weight.

• Procedures and Covid restrictions vary by store. Make sure your equipment is clean.

Eating out

• Avoid bottled water by taking your reusable bottle wherever you go.

• Take a kit with you that contains cutlery, straws, a container, plate, bowl and cup.

• When you order, tell the server you don’t need plastic utensils.

• Ask local food businesses if they allow reusables, and support those that do.

• Find reusable alternatives for packed lunches, instead of plastic bags and film.

• For parties or work events, consider reusables or set up a reusable party pack.

Step Two: Buying Without Plastic

Once your food shop is optimized and you’re ready to level up, you can look at other plastic products in your home.

• Before you buy, ask if you really need it. If it’s essential, is there an alternative with less packaging, or less plastic? As ever, refuse, reuse and repair things before you recycle them.

• As products run out, try a reusable alternative for things like razors, deodorant and periodware. There’s a whole world of products that cost more upfront, but can save money and waste over time.

• Cleaning products: You can reuse containers, and even make your own simple chemical-free cleaners using natural ingredients.

• Gifts: Give experiences, like tickets to a show or a surprise party, rather than stuff.

That’s it! Enjoy it, and make notes of what you find helpful and what’s hard. Reply to this email to send us feedback. If you’d like to share your progress, find us on Facebook or Instagram. #hothousechallenge

How a #Litterati army on Instagram sparked a global fight against litter

By posting pictures of trash, the #Litterati army wants to pressure the world to clean up its act

By Michael J. Coren

It started on a walk in the woods near their home in Oakland, California, in 2012. Jeff Kirschner’s two-year-old daughter noticed a yellow cat litter tub abandoned in a stream. “Daddy,” she said, pointing into Sausal Creek. “That doesn’t belong there.” In the weeks afterward, Kirschner couldn’t see his neighborhood the same way.

“All I saw was trash everywhere,” he says. So he began taking photographs. A lone cigarette butt. An Almond Joy wrapper. McDonald’s coffee cups. Lids. Straws. And on and on. He posted the images on Instagram. Eventually he added the hashtag #litterati, and told his family what he was doing. They began to post their own photos of trash. Others began to notice. Then someone from China posted an image of trash with the Great Wall in the background, and used the same #litterati hashtag.

Litterati founder Jeff Kirschner: Photo: TakePart

Several million photographs later, Kirschner says, Litterati’s “digital landfill” of trash photos has evolved into a global community that has photographed and picked up 8 million pieces of trash, and a smartphone app (iOS and Android) powered by artificial intelligence. Litterati’s work is changing how schools buy lunches, companies wrap products, and cities tax cigarettes. Eventually, it aims to create a world free of litter by turning small, individual actions — mapping and disposing of trash— into something impossible for governments and companies to ignore.

Kirschner, who started his career in advertising, has convinced thousands of people in 165 countries to spend their spare time picking up other people’s rubbish. He applied what he knew about the subtle art of behavior change. “We’ve had two insights,” Kirschner says. “One is that people are craving a sense of connection. Two, there’s no data [about the litter itself]. What we’ve tried to do is fill those two voids.”

Every photo of trash uploaded to Litterati is processed by a machine-learning algorithm, tagging its location and classifying by object, material, and brand — an aluminum Coca-Cola can, or plastic Capri Sun pouch. It’s accurate enough to identify thousands of types of trash down to the company that made it. Users range from fifth graders to 70 year-olds, and they are devoted: some collect as many as 1,000 pieces a day. Anyone can sign up to challenges that unite litter pickers in their local area.

Big Tobacco vs. San Francisco

Since the 1950s, more than 8 billion tons of plastic trash have been thrown away. Only 9% of it has been recycled. We’re now on track to toss 12 billion more tons by mid-century. Amid this tsunami of plastic waste, picking up trash on the street can seem pointless. But something powerful happens when millions of individual pieces of trash are identified and mapped for everyone to see.

In 2009, San Francisco was spending an average $8 million per year cleaning up discarded cigarette butts and tobacco products off its streets. It’s a global problem. Tobacco products make up nearly a third of all litter washing up on beaches around the world.

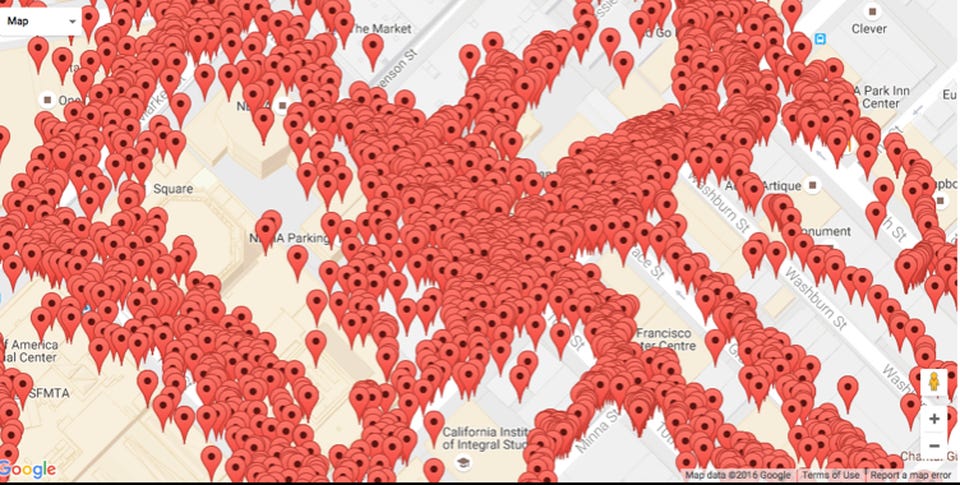

So San Francisco levied a 20 cent tax on the 30 million or so packs of cigarettes sold in the city each year. The tobacco industry retaliated in court, arguing that the city's method of collecting data — pencil and paper clipboard surveys — wasn’t accurate enough to justify the tax. The city turned to Litterati for help. And over five days, its users set about documenting 5,000 pieces of litter across 32 locations, in many cases classifying the debris down to the cigarette brand. As a result, the judge allowed the city to double the tax.

Litterati users documented litter across San Francisco, helping the city take on big tobacco — and win

Litterati had another victory in The Netherlands. Anta Flu is one of the country’s most popular throat lozenges, and each one is individually wrapped in green plastic. Each year, more than half a million Anta Flu wrappers are estimated to end up as litter.

Activists Dirk Groot and Merijn Tinga, who’s known as the “plastic soup surfer,” mobilized the Litterati community to pick up tens of thousands of Anta Flu wrappers. In 2018, the pair met with Jeroen Overing from the manufacturer Pervasco, presenting him with bags of the discarded wrappers, a national map of the company’s litter, and a “bill” for the national cleanup. In October 2019, as part of its ongoing effort to trim waste, the company announced it was dropping plastic for wax-coated biodegradable paper wrappers along with adopting efficient packaging and shipping materials.

Waste as a product flaw

We’re all familiar with a company's liability for its products — but less familiar with liability for its trash.

First introduced in Sweden in the 1990s, the principle of “extended producer responsibility” (EPR) has now spread around the world. EPR means manufacturers must bear the cost of disposing of their products, rather than passing it on to local governments, customers, and the environment. When products reach the end of their life — and in the case of single-use plastic packaging, immediately after we buy it — only a fraction of these materials are ever recycled.

EPR flips the incentives. Manufacturers must internalize and reduce the cost of their trash either by recycling, or making their materials less harmful in the first place. France, the Netherlands, and Germany all began implementing stricter EPR in the early 1990s. In the US, more than 70 EPR laws were enacted between 1991 to 2011.

Not all of them have worked. Voluntary programs without strict enforcement have yielded “disappointing results” according to a study by Harvard Kennedy School focused on e-waste. Others, like British Columbia’s mandatory ERP program, have seen collection rates soar from about 57% to 78%, much of it funded by the producers themselves (though critics warn the lack of transparency makes it hard to evaluate).

But our old approach to recycling plastic is probably over. China’s ban on dirty and poorly sorted recyclables in 2018 meant plastic imports fell by 99% overnight — virtually extinguishing the global market for recyclables. Suddenly, 111 million tons of plastic had nowhere to go, and cities were forced to reevaluate who should really be paying to clean up trash. “Asian markets for... recyclables have effectively closed,” states Oregon’s King County, which is exploring an EPR program. “Competition for reliable domestic end markets is intense, contamination rates are up, and difficult-to-recycle materials are added to the system regularly.”

That’s forcing other states, including California, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maine, New York, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington, to examine legislative policies for ERP. In Congress, similar legislation was introduced in February 2020. And a ban on single-use plastics recently passed the European Parliament.

Starbucks: ‘What are you going to do with all this data?’

We’re entering an era when packaging that ends up as litter is not seen as an unfortunate accident, but a design flaw by manufacturers themselves. Every brand in the world has a unique litter fingerprint, and groups like Litterati are determined to make it visible to everyone. Kirschner recalled when Starbuck’s environmental director called him several years ago after noticing how much of the company’s trash was being cataloged on the app. “I see that you have a lot of data from us,” the executive told him. “What are you planning to do with it?”

For now, Kirschner says, Litterati is giving the data to anyone who wants it. Cities, companies, and schools are all working with the app to better understand their litter problem, and to work out solutions. Each day, 20,000 new pieces of trash are added to its digital landfill.

“We can enable the carrot, and we can enable the stick,” says Kirschner. “Our intention is not to shame anyone. Our intention is that there has got to be a better way. Because the current situation sucks.”

• Got two minutes? Tell us how to make Hothouse better

Hothouse is a weekly climate action newsletter written and edited by Jemima Kiss, Mike Coren and Jim Giles. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read.