Cities on hills and shimmering lakes: A daughter's Earth Day tribute 🌎

Lessons from a Renaissance Man 📜🪶🔬

Climate Solutions // ISSUE # 105 // HOTHOUSE

Sometime back in 2022, when Michael Coren was still building Hothouse with me, he once remarked how I seem to just ‘see’ things—from editorial taste or direction to business ideas. Others have commented on how I seem able to put words to things that make the intangible and abstract, concrete and vivid. I imagine I have my father to thank for much of that.

With that, this Earth Day, I am going to share something a little different, something more personal—a piece I wrote in honor of my Dad, a man more in tune with and reverent of the natural world than anyone I’ve ever known.

My father, Dr. Gregory Peter Bambenek, passed away last month, on March 26, in Duluth, Minnesota. Because his story has shaped so much of my own, and thus, by extension, Hothouse, I think it’s important to share his story with you.

My father was many things: a psychiatrist by trade, a naturalist by passion, a scientist and an inventor, and a bit of an archivist.

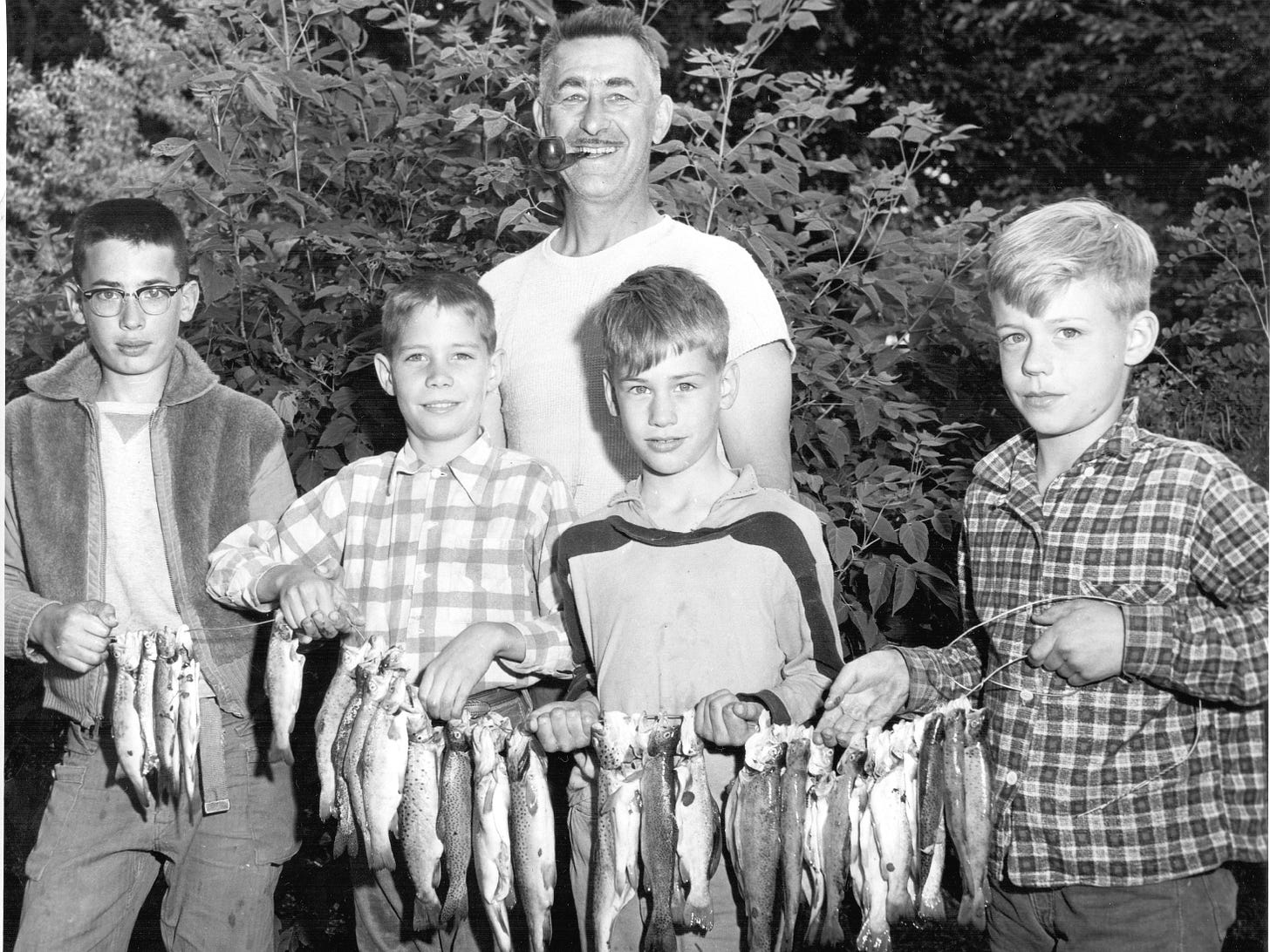

Growing up, my Dad accompanied his father, Hubert “Hub” Bambenek, on his days off in Winona, Minnesota, to catch catfish commercially on the banks of the Mississippi by summer and to trap fox and mink in the dead of winter. My grandfather, himself an avid naturalist, taught my father well. He, in turn, taught me.

A couple of years ago, my father was sending me links to old home videos. Clicking one, it took me to a grainy and sun-soaked recording of myself at age 6, holding a mushroom cap plucked from the stem. I could hear my father’s voice in the background: he was teaching me about mycelium, the underground network of tender threads that mushrooms use to communicate and transport nutrients.

In many ways, the clip gets to the essence of my childhood.

Our father imparted his passion for science and the natural world to my three brothers and me.

Each spring, we waited for the first temperature fluctuations to tap for Maple syrup. Come June, we made the long drive to southern Minnesota to forage for morel mushrooms. We learned which plants were edible, which were medicinal, and which were poisonous. In the winter, my family fished on ice and trapped beavers along frozen rivers.

We learned how to read the smallest details to understand the environment around us, like how tender ramps pushing up through the earth are always the first sign that winter is finally subsiding in northern Minnesota. We were taught to study the profile of the woods as we navigated deeper—to note natural markers, like an eagle’s nest or a sole birch tree in a forest of poplar, so as to not get lost, and to use the high-tech tool of the digits of our own hands to track in 15 minute increments the light left until sundown.

I also want to share my father’s story with you because, in several ways, I believe elements of how he lived his life are climate solutions, too. His oral storytelling of adventures and mishaps, for instance, had the potential to shape the lives of anyone willing to listen, opening them to curiosity and awe. His openness to indigenous and Eastern knowledge systems created space to question the conventional, while his eagerness to educate and expose any children within his orbit to the natural world planted a seed; studies show that exposing children to the natural world has the strongest correlation with creating adults who care about protecting the environment.

I also believe sharing his story with you is a kind of climate solution of its own. Remembering and honoring the legacy of people and place is one way we reground ourselves and see beyond our own noses, to remember that we are custodians of land and memory alike for generations yet to come. This mirrors an Indigenous concept known as the Seven Generation principle, which urges individuals to carry the knowledge and wisdom of past generations forward for the stewardship of the next seven generations.

Telling our stories and revisiting history may not stop us from making the same mistakes. But it gives us a map to how we wandered off course—and that map, if we’re paying attention, might just help us find our way back.

When I was a little girl, I used to think that all cities were made sitting on a hill overlooking a Great Lake. Why would I not? Driving around Duluth growing up, Lake Superior was always within sight, gleaming up at us from the bottom of the hillside.

It wasn’t until I got older that, to my surprise, this turned out not to be the case. Very few cities, in fact, are sitting atop a hill overlooking a Great Lake.

And the last few weeks, I’ve been reflecting on how that memory speaks to something true about my Dad, too.

You see, I think for anyone who had the chance to meet my father, Greg Bambenek, Dr. Juice, they probably knew right away that there was something about him. But I think for me, as his daughter, that’s only coming into clarity for me over these last months and years. Because you see, for me, he was simply my father. The same way I grew up thinking that all cities were planted on top of a hill, you don’t always think about who someone is when they’re simply a fixture in your life.

It’s simply the water you’re swimming in, the air you’re breathing.

Of course, my father invented a fishing scent and took the Vikings out for Salmon and Lake Trout on Lake Superior. Of course, he conducted anthropological research with medicine men in Belize and Mexico, studied acupuncture in Taiwan, and researched marijuana use in Vietnam on behalf of the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. When the U.S. was landing a man on the moon, he was traipsing around Nepal, India, and Egypt. Of course, he was a beautiful guitar player, an excellent chef, a steadfast gardener, and could go deep on any topic.

It’s not until grief shifts the focal point of your lens those last few notches that everything comes so sharply into focus.

It turns out it’s not every day you get a father born in 1947, a world traveler, anthropologist, entrepreneur, and psychiatrist all rolled into one.

As one young man put it, our father was a man who never learned to sit still. Son of a hairdresser and a fireman, trapper, and commercial fishermen on the banks of the Mississippi, Dad was a Renaissance man—as close as the world might ever come to a cross between a real-life Indiana Jones, a walking encyclopedia, and a relentless inventor. I can vividly recall him always tinkering in his garage late into the night when we were growing up, right below my room. He was relentlessly curious about the advancement of science, and I know he would have loved to see all that humanity has yet to accomplish.

This is all to say, I inherited, or just as likely, learned, more than a few quirks from our Dad. I think we all did.

From my Dad, I inherited an intrigue in China, violin, guitar, travel, an interest in science, and my way around a camera, thanks to a red, yellow, and blue colorblock plastic film camera one Christmas when I was about 8.

One more intangible quirk I inherited from our father, in particular, would be an ability to see the interconnectedness of everything. The trouble with that is, when you can see the interconnectedness of everything, you can see everything, all the possibilities. And when you see all the possibilities, you want to pursue all of the possibilities.

And that he did. It was a running family joke that Dad was always ahead of the curve by a decade or two—from biodegradable fishing lures to underwater fish speakers. And we have the archive of home videos on YouTube from the early aughts to prove that he was convinced videos were the next big thing, well before TikTok blew up.

He embraced the validity of Indigenous shamans, medicine men, and acupuncture, long before Western medicine caught up, defending the legitimacy of Mexican shamans even in his final weeks. He understood and saw the validity of the unconventional and the ancient long before modern medicine and knowledge were ready to contend with that reality. He had a reverence for nature and wildlife foreign to our modern times. Growing up hunting, he taught us to sprinkle tobacco over the body of any deer whose life we took, giving thanks in the way the Ojibwe always have.

This quality also made him hopeless at prioritizing. This was true right up until the end. He had finances to take care of and a book project he and I were working on together. Instead of working on these things, he figured out how to make ice cream out of the milk and sugar he was supplied with at assisted living. I had made the mistake of introducing him to Ben and Jerry’s Half Baked ice cream a couple of months prior; he’d never had such a thing, and he was in love. So he absorbed himself trying to recreate that Half Baked ice cream flavor in the comfort of his own apartment. Never mind that I brought him resupplies of actual Half Baked ice cream on the regular. He just wanted to be experimenting and conducting science, right up until the very end.

And while I share his relentless curiosity, I like to think I’ve gotten a little better at prioritizing than he ever did. He acknowledged as much himself in the last few months, “I never really did figure out prioritizing. I just kind of always pursued everything.” Maybe he never had to learn to prioritize; somehow, he was simply able to do it all, until he wasn’t able to anymore.

Even as his lack of prioritization skills finally seemed to catch up with him, he was so fully engaged in life, shaping the world right up until the very end.

Ten years ago, at 67, my Dad was still trekking around China and Thailand with me, eating deep-fried scorpions (I could never), and riding elephants. Not two weeks before he passed, my Dad proposed a different kind of trip. He asked me if I wanted to take psilocybin mushrooms together. Mind you, my father and I had, of course, discussed psychedelics throughout my life; he was Dr. Juice, after all, but he’d never before proposed we actually take them together. But that’s just the kind of man he was—always ready to go on one more adventure.

We never did get to take that trip together.

But I think that’s part of his story, too. He was always down for one more adventure, one more trip, one last experiment or idea.

The night he entered the hospital, I was sitting with him telling him a story idea I’d like to write for a magazine, and he was giving me ideas on immunologists to reach out to to interview. I told him about book ideas and talks I’d like to give. He was even consulting me on what medications to take as I was navigating for my own health journey up until 72 hours before his passing. And he certainly didn’t let the fact that he wasn’t a journalist stop him from proposing astute ways to incorporate artificial intelligence into my career as a journalist these last few months.

Our Dad could’ve lived one hundred lives and he would have filled them all up to the brim.

In one of our final days together, Dad played me old home videos on the screen in his assisted living apartment. In one scene, I’m scrambling up steep cliffs in Lake of the Woods to collect blueberries; in another, Connor, Dad, and I are at the tallest heights of a ski jump in Northern Michigan. I don’t look so comfortable with the height. In the next video, we’re spelunking deep in some mine shaft, and, in yet another, Connor is playing with a garter snake twisting in his hands, and I’m right there with him, interacting and petting the snake. What stands out to me in that video, and the rest of them, really, is how timid I look. It’s evident I’m quite scared of the snake and uneasy with the great heights.

Watching these old videos, I realized my Dad's greatest gift was teaching me to do things, even if afraid. He was always right there, making the unknown feel approachable, welcome, even.

It’s something others have remarked about me as an adult. For those who don’t know me, I’ve spent most of the last 8 years pursuing a career as a journalist in New York City. Fed up with traditional media, four years ago, I co-founded a journalism endeavor to report on climate solutions, which I now operate solo, called Hothouse. But others have often remarked on my bravery for the way I’ve approached my life—for the gall I had to simply move to New York with less than a few thousand in savings and no real work lined up, or my decision to gallivant around Southeast Asia solo.

They’ve remarked at my bravery, but it’s never felt like much to me at all. And I’m imagining I have a great deal to thank my Dad for in that department, that he taught me to simply do things regardless of fear, to push my boundaries. I’m sure there’s a double-edged sword, and this trait comes with a little more pain than if I had learned to simply trust my fears and doubts. But then I might have shied away from the world; I wouldn’t have dove headfirst, straight into the deepest waters, and experienced life as raw and real as I have.

I know I live my life more fully, for he was my Dad. I know we all do.

Our Dad is the reason I’m as weird as I am. A little bit feminine, a little bit masculine. Drawn to aesthetics and esoteric questions alike. Our father is the reason I’ll probably never care about traditional markers of success; he showed us a way of seeing the world that is so far off the beaten path, because he was eager to take us there, to show us the entire world.

When I was a little girl, he encouraged me to follow in the footsteps of his good friend, Bob Briggs, and become a dentist or maybe an orthodontist. And Bob was cool, Bob had his own single-prop plane, which he once took Dad, my twin Connor, and me up high in the air.

I think when I exhibited interest in writing from an early age, writing poems or short stories, my Dad was frustrated or anxious about what kind of security that future could offer me.

But he failed to understand that not only did he instill in me the confidence that I could do anything I wanted, irrespective of how much it terrified me, but he equipped me with the very raw ingredients to pursue writing to begin with.

You see, my Dad was an excellent storyteller. Nothing gave him greater pleasure on this planet than telling a good story. So if he was anxious about my proclivities, I’m afraid he only had himself to blame. When I was little, Connor and Parker would usually fall asleep a little earlier than me during weekends at a cabin on Crow Lake or out camping along Lake Superior’s South Shore.

And, in those late evenings, I’d make my Dad tell me stories. About warriors in China who used straw men to collect the arrows from outside attacks, about Taoism, about alien sightings, about asteroids, and about life on Mars.

And today I realize that when I research and write, his voice and presence come through in my curiosity and the delight in the telling. My writing is now another way he lives on. As is Parker’s passion for the outdoors, Connor’s adeptness at tinkering, and Jacob’s thirst for adventure.

I spent two of Dad’s last nights with him at the hospital, sleeping in the cot. The night before he passed away, he was up at 3 a.m. I played him some Beatles music videos to soothe him. As I was drifting back to sleep myself a little while later, I had the most visceral feeling of a dog licking my face, a sensation so strong that it woke me up. It felt like warmth and sunshine. I’d never had such an overwhelmingly vivid dream before. I’d like to think that it was Quincey, our Red and White Irish Setter growing up, offering reassurance from the other side.

I’m not religious, but my Dad made me open enough and with enough humility to believe that we don’t know everything that we don’t know.

For most of your life, your family is simply there. There’s not much need to break out each component and turn it over in your hands.

But grief has a funny way of acting like the focal length on a camera. Over the last few months and years, the meaning our Dad has had in my own life has been slowly coming into focus. And it’s as if losing him was the lens at last clicking into place, until everything becomes crystal sharp.

I had the privilege in the last few months of articulating some of what he meant to me directly to him, but I wasn’t prepared for all that would click into place once he was finally gone.

I can’t speak for my brothers, but at least for me, he took a little girl, timid in the world, and made her relentlessly curious and unflinchingly unafraid.

Of course, that kind of unabashedness has its costs. I’ve had more than my share of heartbreaks and heartaches, maybe I’ve been a little too open, a little too curious about the world at times. But I don’t have many regrets because my Dad empowered me to pursue my own self-actualization to its very end.

That said, at one point or another, I think our father had contentious relationships with each of us. Anyone who knew my father knew he was a stubborn man. He also taught all of his kids to be so independent and to question everything, including him. We made a joke at his bedside the afternoon before he passed, about how he was loving but always so stubborn, and about how he should have thought about that before raising such independent kids.

Even if it went against his personal interests, he raised us with the tools to navigate this world on our own.

Jacob is 45, Parker is 34, and Connor and I just turned 30. It’s something I’ve long known was coming, but it still feels like a tragedy to lose a parent so young. But if anyone equipped his children with a lifetime of wisdom, tools, and knowledge before he had to go, I’d say our Dad did.

And I know he touched lives well beyond his own kids. He was a mentor to young men, ones oftentimes unconventional, creative, outdoorsy, or entrepreneurial in their own right, just like him.

Dad was obstinate and brilliant and always welcoming. He had a contagious enthusiasm for life, and he always had the capacity for others—he was a good listener and reasoned through situations like a good detective.

In the last few weeks, I asked him why he listened to my ideas when others often might be quick to dismiss my perspective as a tad paranoid. And what he said simply stopped me. He said, “I just think through the things you say and they make a lot of sense.” He saw me.

If it’s not clear by now, he was my thought partner. I will miss my thought partner, co-conspirator, and best friend, in all his wild relentlessness.

He was an amazing teacher and storyteller, but somehow, curiously, not always the best communicator.

We talked about the messiness of human relationships a lot in his last few months and years. How easy it is to make mistakes in the moment, how there’s oftentimes such clarity in hindsight that we would’ve traded anything to have had in the moment.

It’s a double-edged sword, isn’t it? He was full of contradictions. But our worst qualities are oftentimes simultaneously our best qualities. I’ll miss our deep discussions about philosophy and people and ideas, but maybe not about politics. There are some bridges we can’t always cross.

I recently lamented to a friend over the phone that the friends I’ve made as an adult in New York City will never know my father, and she said, ‘True, but would they ever really have understood?’ And she’s right, I don’t know that anyone could ever convey the reality of who our Dad was in words alone. He was someone you had to experience.

When I was a little girl, I didn’t know Great Lakes weren’t a fixture of every city.

I didn’t realize how far out and singular our father was, either.

But I think Dad would have liked that idea about all cities being built atop hills overlooking shimmering lakes. Because, in his world, possibility stretched far and wide, beauty was always just around the bend, and nearly anything could be over the next hill.

◆ I hope this piece offers a glimpse into half of the lineage that shapes my thinking and inspires you to reflect on the legacies that shape where you came from and inform where you are going, too. Happy Earth Day 🌎

◆ If you feel so inclined, memorials are welcome to erect a bench along Lake Superior’s North Shore in my father’s memory 🌼

◆ If anyone has insights into book publishing they’d like to share for the book I’m working on for my Dad, I’m all ears: cadence@hothouse.solutions 💌

Love this! "all cities were made sitting on a hill overlooking a Great Lake" -- such a beautiful metaphor for how our perspectives are shaped by those who raise us.

What a lovely tribute to your father and to the remarkable publication, Hothouse.